TIMBERLAND, SASK. — There’s a chill in the autumn air as Anita Smith stands in her garden harvesting the last cucumbers off the vine.

As she rustles through the wilting foliage, ensuring she pulls every single fruit before frost sets in, she reminisces about her earliest experiences of preserving.

READ MORE:

- Harvesting memories: Leo Gaboury reflects on farming’s evolution

- Meet the Saskatoon artist preserving the dying art of bobbin lace

- ‘A hat for everybody’: Sask. milliner instills confidence with fancy hats

“I guess I began really when I started washing jars for my mom when I was a little girl,” she says, her hands moving quickly as she speaks, seemingly impervious to the tiny prickles covering each garden-grown cuke.

She smiles softly as she continues, “I would tell her, ‘Ugh, I’m never gonna do this when I’m older.’ Now I wash more jars than my mom ever made me do — by choice!”

Each fall Smith preserves hundreds of pounds of garden produce through methods that have been passed down through the generations.

Much of Smith’s farmyard is occupied by an immense garden plot. She grows a variety of fruits and vegetables, and preserves as much as possible each fall. (Brittany Caffet/650 CKOM)

Smith lives on a farm in Timberland, a small hamlet 9 miles east of Leoville, Sask. Much of her farmyard is occupied by an immense garden plot that she spends countless hours tending to each summer. As the air gets crisp in the fall, she strives to preserve as many of the fruits of her labour as possible.

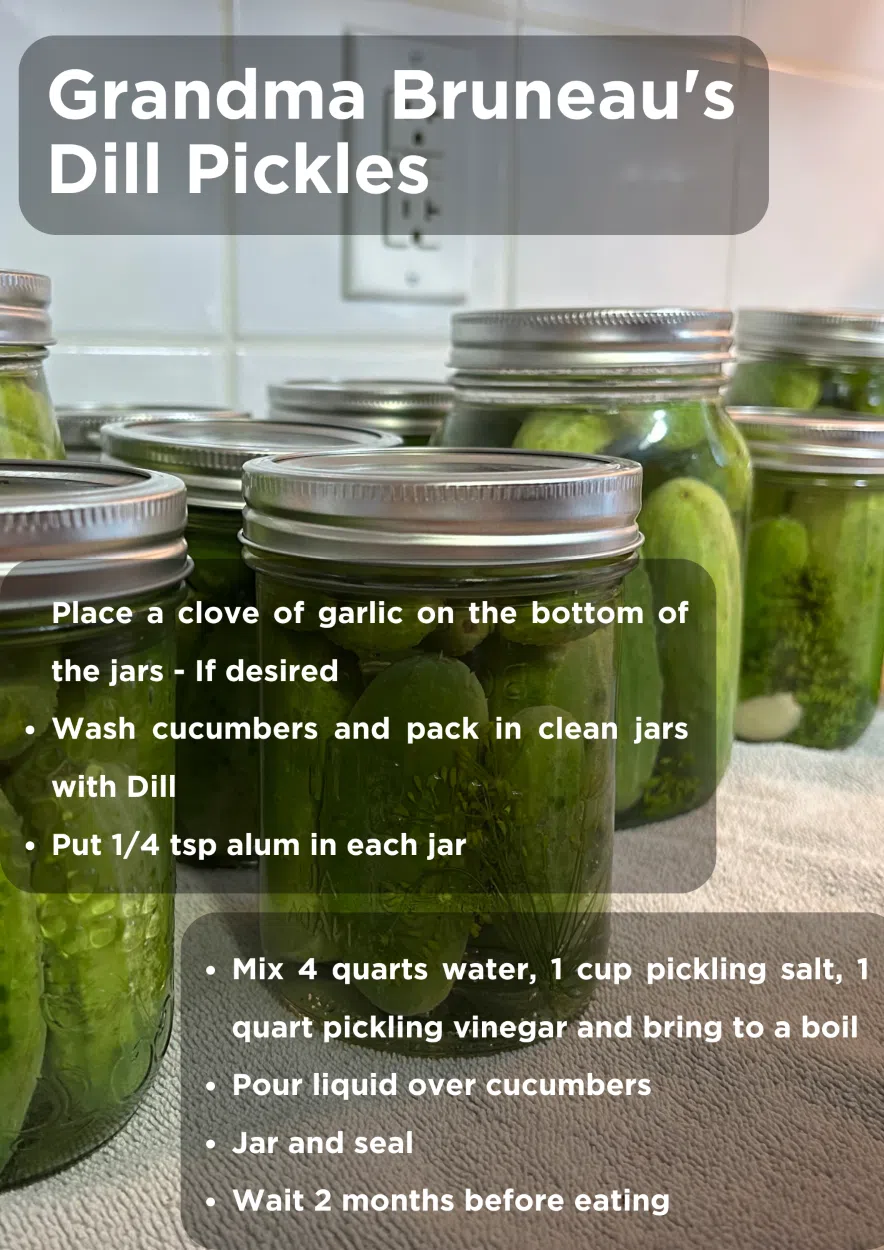

Grandma Bruneau’s Dill Pickle recipe. (Graphic by Céline Grimard, Photo by Brittany Caffet)

“I do green beans and carrots and corn the old-fashioned way, with glass lids and rubber rings in a water bath on top of the stove,” she explains proudly. “Not too many people do it anymore.”

Smith’s repertoire of canning recipes is vast. She makes jams, jellies, relish, mustard beans, canned whole fruit and has even tried her hand at preserving fish. But she says her favourite thing to make is her grandmother’s dill pickles.

While Smith’s grandmother only used larger cucumbers to make dill pickles, her mother included small pickles in the jars. She says she and her siblings would fight over the “baby pickle.” (Brittany Caffet/650 CKOM)

“My mom didn’t have a pickle recipe, so my dad took her to go see his mom and get her recipe,” Smith says, her eyes alight as she shares the family lore tied to the beloved recipe.

She chuckles, “My grandma only spoke French, so my mom couldn’t really communicate with her. My dad had to translate the recipe into English. So, good on Dad for getting it right!”

While Smith’s father did manage to properly translate the ingredients and ratios, her mother made one notable change to the pickling process.

“My grandma would only do bigger dills, but my mom would put the little baby pickles in amongst the larger pickles,” she says. “It was always a fight to who got the baby pickles. They were the best. When me and my sisters and my brothers started canning, we made jars specifically with only baby pickles in them. When we took out a jar, we didn’t have to fight over who got the baby pickle.”

Smith’s repertoire of canning recipes is vast. She makes jams, jellies, relish, mustard beans, canned whole fruit and has even tried her hand at preserving fish. But she says her favourite thing to make is her grandmother’s dill pickles. (Brittany Caffet/650 CKOM)

Smith is a mother of two and says while her children haven’t experienced fighting over the baby pickle, they have also developed an appreciation for this family recipe.

“I’ve already taught my daughters how to can, so I know that this recipe will be passed on not only to my daughters but maybe their children,” she says.

She reflects on the importance of preserving family recipes and customs, saying, “I read this one thing that said it only takes two generations to lose family traditions. Once you skip a generation, it’s very easy for the next generation to skip it too. Then before you know it, it’s lost. And then it’s hard to pick back up because the recipes are gone, the knowledge is gone — everything just disappears.”

Though canning is a labor-intensive process, Smith firmly believes the effort she invests each fall is worthwhile. For her, the only part of this family tradition that should disappear is the last baby pickle.