Allen Sapp made his final visit to the gallery that bears his name shortly before he died in 2015.

“I hadn’t seen him in a while and I wasn’t sure what the state of his health was. We had a school group here… and they had just finished a tour,” recalled Leah Garven, the gallery’s curator.

“He was sitting right over there in the wheelchair. The group leader was leading them out. They were like ‘Shhh… We’re going to go. We don’t want to disturb him,'” said Garven.

Sapp noticed the children quietly filing out of the gallery and called out, motioning for the group to join him.

“He asked for his drum, and he sang. He sang to them,” Garven said, tears welling in her eyes as she recalled the warm, welcoming nature of the artist whose works have left a resounding impact on the province he called home.

Allen Sapp visited the gallery that bears his name shortly before he died in 2015. He played his drum and sang to a group of schoolchildren visiting the gallery. (Submitted)

The Allen Sapp Gallery has recently been nominated for provincial heritage property designation, an honour reserved for places connected to some of the most significant stories from Saskatchewan’s past.

The man behind the gallery

Allen Sapp was born in 1928 on Red Pheasant Cree Nation in north-central Saskatchewan.

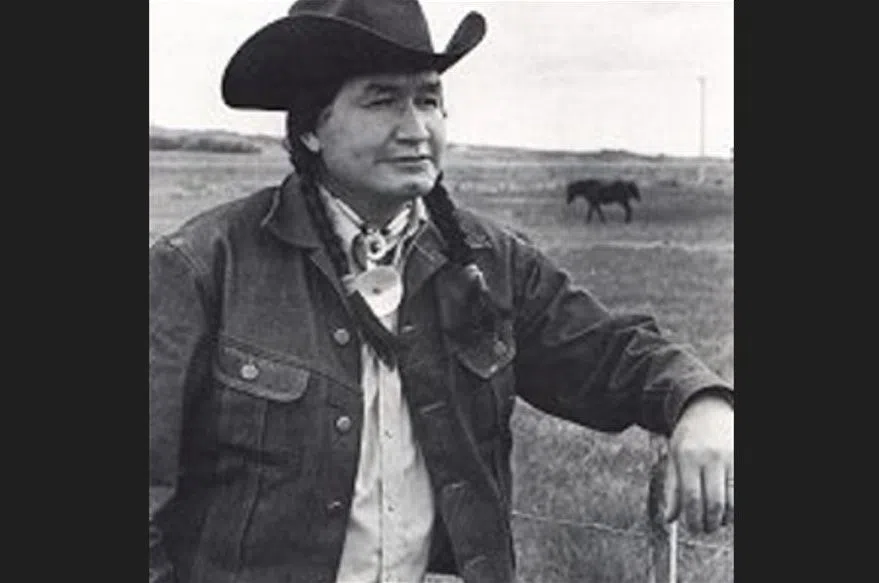

Allen Sapp’s aunt bestowed him with the Cree name Kiskayetum, meaning ‘he perceives it.’ (Submitted)

“In his early life, he was a sickly kid who couldn’t play with the other kids,” Garven said.

Sapp’s aunt bestowed upon him a Cree name — Kiskayetum, meaning ‘he perceives it.’ Although he never learned to read or write, Sapp expressed himself through drawing and painting the events he observed unfolding around him.

“He missed out on playing hockey and soccer, but he witnessed them playing. He watched the world go by and recorded it in these paintings,” Garven said.

Sapp’s paintings provide a window into his early life on the First Nation and are revered as an honest representation of what daily life was like for the Plains Cree people.

Along with dozens of works of art, the gallery also displays items used by Sapp while creating his paintings. (Alex Brown/650 CKOM)

“His grandparents were the last generation to live the old ways. They had the ceremonies that were outlawed, kept secret, and they passed those ceremonies and a lot of protocol down,” Garven explained. “Allen has recorded that in the paintings, and sometimes his paintings would be used as reference for resuming those traditions.”

Sapp moved from Red Pheasant Cree Nation to North Battleford in 1963. Though he was no longer surrounded by the familiar people and landscapes of his childhood, he continued to create art that depicted the humble simplicity of his life on the First Nation.

As the years went by, Sapp continued to preserve his childhood memories on canvas, often creating one or two new works of art daily. In 1966 he went to the North Battleford Medical Clinic to sell some of his paintings and met a man who would help change his life forever.

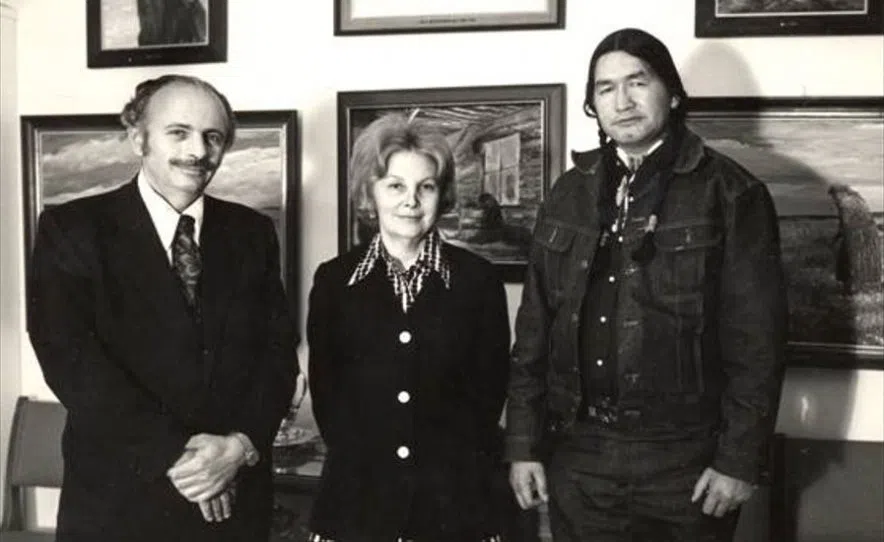

Dr. Allan Gonor and Ruth Gonor were great friends and supporters of Allen Sapp. Many of the pieces displayed in the Allen Sapp Gallery are from the Gonor collection. (Submitted)

Dr. Allan Gonor immediately recognized Sapp’s talent. He and his wife Ruth reached out to professionals around the country for advice on how to help Sapp’s career flourish.

“They felt that the story that Allen told through his paintings was very critical for Canadians and people from around the world to get to know and learn so that we had this better insight into First Nations culture and sharing the land,” Garven said, “which is what Allen’s paintings are all about.”

Sapp’s first major exhibition was held over the Easter weekend in 1969, sparking an explosion in his career. Thousands of people streamed through the Mendel Art Gallery in Saskatoon to view Sapp’s works. The majority of the pieces sold on the opening night.

Allan and Ruth Gonor continued to be enthusiastic supporters of Sapp in the following decades.

“They were truly good dear friends who shared a lot with each other. They shared a lot of support and love,” Garven said. “I like to think that their friendship was an early act of reconciliation that led this gallery to play a role in reconciliation in this province through many of its partnerships over the 35 years that it’s been open.”

A ‘larger-than-life’ Saskatchewan icon

Over his many decades in the public spotlight, Sapp became an unmistakable figure to people around the province and beyond.

“He loved his clothes. He was a man of fashion. He liked to be well-dressed in cowboy gear, and he drove a Cadillac with long steer horns,” Garven recalled with a laugh. “He was a larger-than-life character.”

Allen Sapp is remembered as a world-renowned painter and a man of fashion. He let his hair grow long, plaiting it into neat long braids daily. He would top his outfit with a stylish cowboy hat. (Submitted)

Sapp was recognized greatly for his contributions to his community not only as an artist but as an individual. He received the Saskatchewan Award of Merit, was appointed an Officer of the Order of Canada, and was awarded an honourary doctorate degree from the University of Regina among many other recognitions.

Through all the accolades and praise Sapp was showered with over the decades, he remained steadfastly humble.

“He was very proud of this gallery, but he wasn’t a vain man. He would visit the gallery three or four times a week because, I think, in a way it was kind of his payback. He loved visiting with the visitors that were here, especially the schools,” Garven said, a smile spreading across her face as she recalled Sapp’s many stops at the gallery.

“He really loved working with the students, and he would take over the tour! English wasn’t his first language, so he would communicate with them through the drum,” she said, motioning to Sapp’s drum, which hangs on a wall in the gallery. “We didn’t always know when he was coming because he was in a long-term care home. He would just show up and we’d say ‘Oh, Allen is here!’ It was wonderful.”

Sapp’s paintings provide a window into his early life on the Red Pheasant Cree Nation and are revered as an honest representation of “Northern” Plains Cree people’s daily life. (Alex Brown/650 CKOM)

From NYC to NB: A Carnegie connection

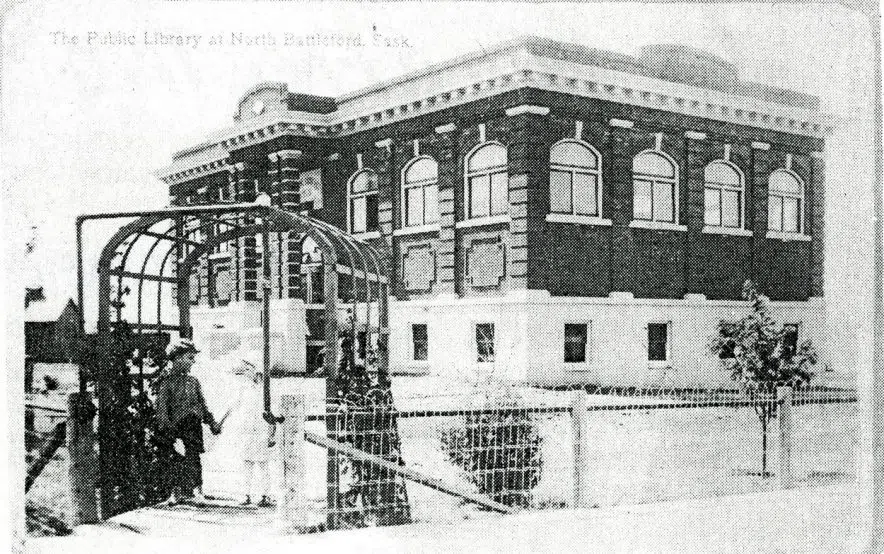

The building that houses the Allen Sapp Gallery was built in 1916 through a $15,000 grant from the Andrew Carnegie Foundation.

Many will recognize Carnegie’s name from the iconic Carnegie Hall in New York City. The construction of the well-known music hall was funded by the Gilded Age businessman and philanthropist.

The building that houses the Allen Sapp Gallery was built in 1916 through a $15,000 grant from the Andrew Carnegie Foundation. (Submitted)

Carnegie penned an article in 1889 titled “The Gospel of Wealth” and expressed his belief that establishing a free library in any community willing to maintain and develop it was the most impactful way to spend money.

Carnegie awarded over 2,500 library construction grants, building libraries around the world. Money was given to towns that had land available and vowed to provide free access to all residents, regardless of their social standing or income.

“The leaders of the day here in North Battleford were go-getters and made an application. They certainly had a vision for how this community was going to develop,” Garven said. “It was a milestone in the development of the city becoming incorporated.”

With the application granted and the design approved by Carnegie’s personal secretary, construction began on the library — a grand red brick building in the heart of the city.

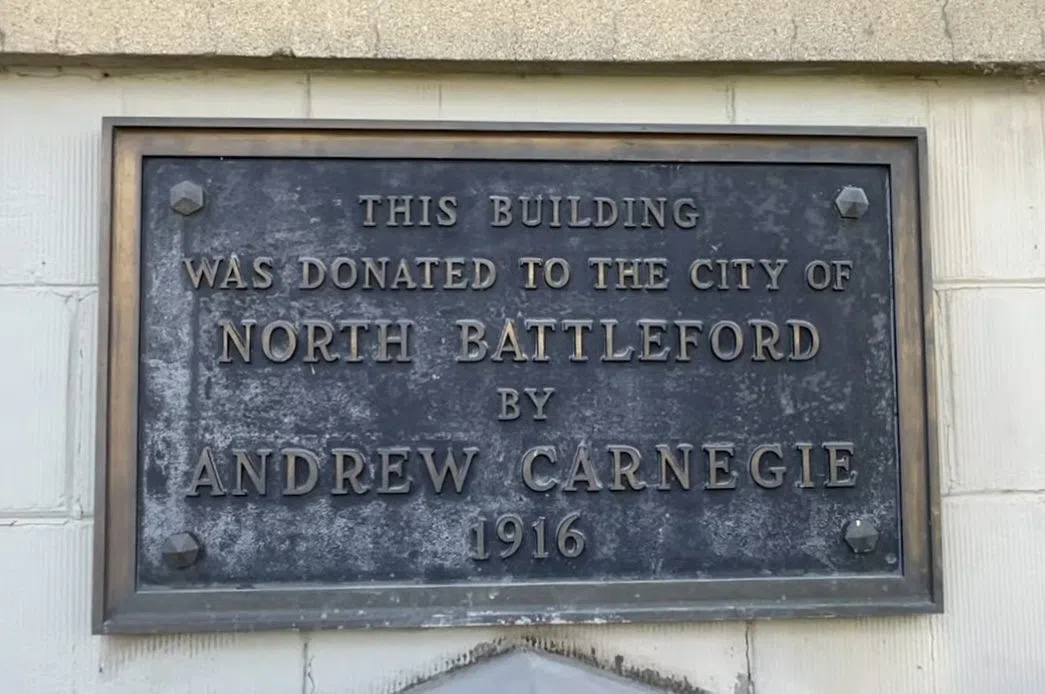

A plaque near the entrance of the Allen Sapp Gallery commemorates Andrew Carnegie’s financial contribution to North Battleford, which was used to build the city’s first public library. (Alex Brown/650 CKOM)

The North Battleford Public Library remained the City’s only public library until 1985 when it was decided the city needed a bigger building to house the ever-expanding collection of books.

“A debate was started on what to do with this building, and through civic leadership a decision was made to convert it into a gallery dedicated to the art of Allen Sapp,” Garven said.

In 1989 the long-closed doors of the North Battleford Carnegie Library were opened, revealing the Allen Sapp Gallery — The Gonor Collection.

“The day of the opening reception for this new gallery, Allen was very emotional,” Garven said. “He was a sensitive guy, but I think he really understood what was happening… that he was going to have a gallery named after him and dedicated to him.”

Listen to Garven on Behind the Headlines:

The path to provincial heritage designation

Last month, Garven formally began the process to have The Allen Sapp Gallery declared a provincial heritage property.

“We currently have municipal heritage designation, but we would like to elevate it a little to the provincial level,” Garven said.

“It would elevate the merit of the building and its history and role in the development of North Battleford… and other than that it’s really just bragging rights,” she added with a laugh.

The Allen Sapp Gallery sits in the heart of North Battleford. Curator Leah Garven is working to have the building declared a provincial heritage property. (Alex Brown/650 CKOM)

Provincial heritage properties are designated by the Government of Saskatchewan. There are currently 56 provincial heritage properties in the province.

Aside from the historic value of the building, Garven explained that the works of art adorning the gallery walls also carry incredible significance.

The Allen Sapp Gallery is the only public gallery in Canada dedicated to an Indigenous artist. Each painting depicts a memory from Sapp’s experiences as what he calls a Northern Plains Cree man. His art opens a window into a way of life that would otherwise be unseen and unknown to so many.

“I had an elder here a few weeks ago and as he was talking to me and walking away he said ‘These paintings they have spirit. They have life, and you can feel them,'” Garven said. “It’s a real, real gift.”

Gallery curator Leah Garven worked personally with Allen Sapp for years. She describes the artist as “a larger-than-life character.” (Submitted)

As she looks around the room, Garven’s eyes are met with reminders of the world-renowned painter in every nook and cranny of the historic building.

The drum Sapp used to welcome the very last group of students he met with before his death hangs on the wall in a place of honour, welcoming all new visitors as they venture into the gallery, gaze upon the paintings, and see the world as Allen Sapp perceived it.