Saskatchewan’s collective bargaining agreement for teachers is very thin, according to the federal body representing teachers.

Heidi Yetman, president of the Canadian Teachers Federation, told Evan Bray on Thursday that teachers have the right to bargain.

Referencing Bill 28 — which spurred a 14-year legal battle between teachers in British Columbia and the government in that province, a battle that ended at the Supreme Court of Canada — Yetman said it’s now known that collective bargaining is a fundamental right and one that teachers have.

READ MORE:

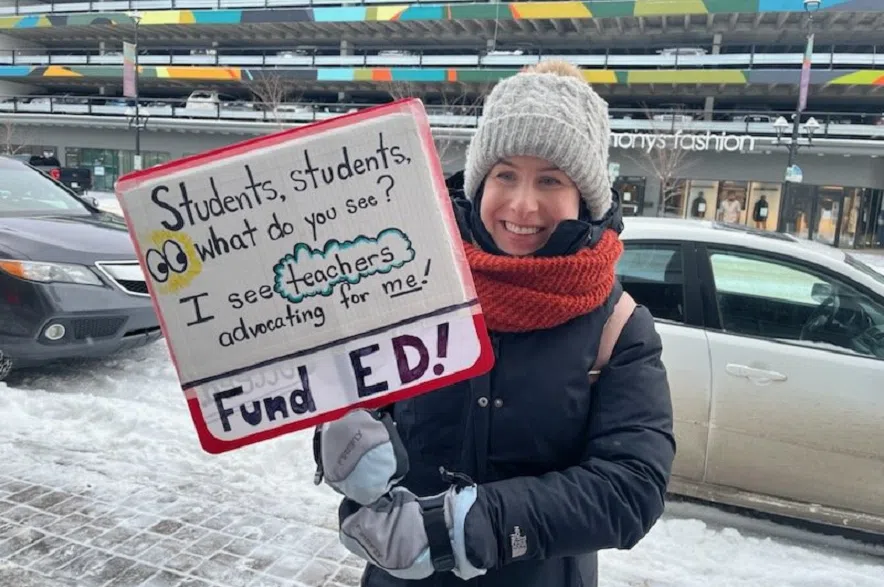

- Teachers hit picket lines Wednesday in Saskatoon as STF strikes continue

- STF president says she’s ‘cautiously optimistic’ about contract talks resuming

- STF suspends job action after gov’t invites union to resume bargaining

Armed with that information, Yetman called the collective agreement in Saskatchewan thin.

She said she was “quite amazed” at how little is in the agreement between teachers and the Government of Saskatchewan, with nothing relating to workload or working conditions — which would include issues like class size and classroom complexity — being referenced.

Classroom complexity and class sizes are not problems unique to Saskatchewan, Yetman emphasized. In addition to the Bill 28 challenge, teachers in Quebec were out on strike just before Christmas in an effort to get more money from the province, despite having their own language in that collective agreement that stipulates monies will be provided by the province specifically for class composition.

School boards in Quebec are tasked with calling upon the province to receive those monies because of certain classrooms facing difficulties. A discussion between the teachers’ union and the school board then ensues to decide how to help a specific class.

For example, a classroom with a significant number of children or several children with additional needs might be split in two and the money used to hire an additional teacher. Special education instructors and educational or teaching assistants could also be hired for certain classes to help with specific students.

Yetman called it “wonderful” to have that money available.

“It’s not one size fits all; it’s money available to do that work to make sure kids are supported,” she said.

In Canada, five provinces have language in their respective collective agreements that allow for working conditions to be considered for teachers. Those provinces are Ontario, New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island, Quebec and B.C.

Yetman, who taught in Quebec, said the agreement has been working well there, and the exact example of a second teacher hired to take over a class that needed to be split in two has been successful.

However, none of these arrangements are perfect, Yetman said, and the perfect amount of money is never available.

She said the most significant consideration is ensuring there is language in a collective agreement that allows for the province to give money to school districts to fund the resources needed for students in classrooms.

“Saskatchewan has no language at all in the provincial collective agreement,” Yetman said.

Further, she acknowledged that teachers feel they must bargain for conditions outside their specific benefit, like resources that affect how they can do their jobs. Yetman agreed with Bray that teachers are presently bargaining for resources that will benefit school boards, though those boards and districts themselves are on the employer’s side of these negotiations across the country.

“Teachers are fighting for the students in their classrooms and they’re fighting to make sure the districts have the funds needed to help those students,” she said.

“This is nothing new,” Yetman continued, sizing the problems up as anything involving students with additional or varied needs being part of a classroom. Those needs, she said, can range from behavioural to learning or mental health and other conditions that impact a child’s ability to learn and focus.

The key, however, is that teachers on the ground who are working with students need to be listened to, according to Yetman. Having had a 23-year teaching career herself, Yetman told Bray that her No. 1 goal as a teacher was to ensure her students succeeded.

“If you have a lot of students with needs and you have no resources, then it’s really hard to get your students to succeed and that’s pretty depressing,” she shared.

Battle of the wages

Another condition Yetman said should be consistently embedded in collective agreements is wages adjusted for cost-of-living expenses.

Inflation rates do continue to rise across the province, she said, and governments are offering miniscule raises compared to the percentages of prices that have increased.

“Everybody should at least be getting cost of living,” Yetman said.

Without that sort of consideration, governments are decreasing the purchasing power of teachers.

Yetman noted wages for teachers are fairly similar across Canada, but everybody in every province who has been at the bargaining table has been requesting the same sort of increase in covering the increased cost of living.