Too much ice buildup on “critical surfaces,” no adequate de-icing equipment available, and a flight crew’s decision to take off in spite of that were factors that contributed to a West Wind Aviation plane crash in Fond-du-Lac in December 2017.

“Ultimately, the cause of the crash was contamination of critical surfaces of the aircraft,” Transportation Safety Board of Canada investigator Eric Vermette said during a news conference held Thursday to discuss the final report into the ATR 42-320 plane crashing after takeoff from the Fond-du-Lac airport on Dec. 13, 2017.

“In addition, the investigation looked at the crashworthiness of the aircraft which contributed to the injuries and ultimately to the death of one of the passengers,” board chair Kathy Fox added. “We looked at the way the operator managed the safety risks of their operation, as well as how Transport Canada conducted its oversight.”

The information is included in the Transportation Safety Board of Canada’s final report. It describes the plane initially taking off from Diefenbaker Airport in Saskatoon and landing in Prince Albert for about an hour before continuing on to the Fond-du-Lac airport.

As the plane approached the northern airport, ice began to build up on the plane and the crew activated the craft’s anti-icing and de-icing systems. The plane was on the ground for 48 minutes and during that time, even more ice built up on the plane.

A cursory check by the plane’s first officer was done before a decision was made to take off. The plane’s captain didn’t look at the plane himself, nor did he try to get the plane de-iced.

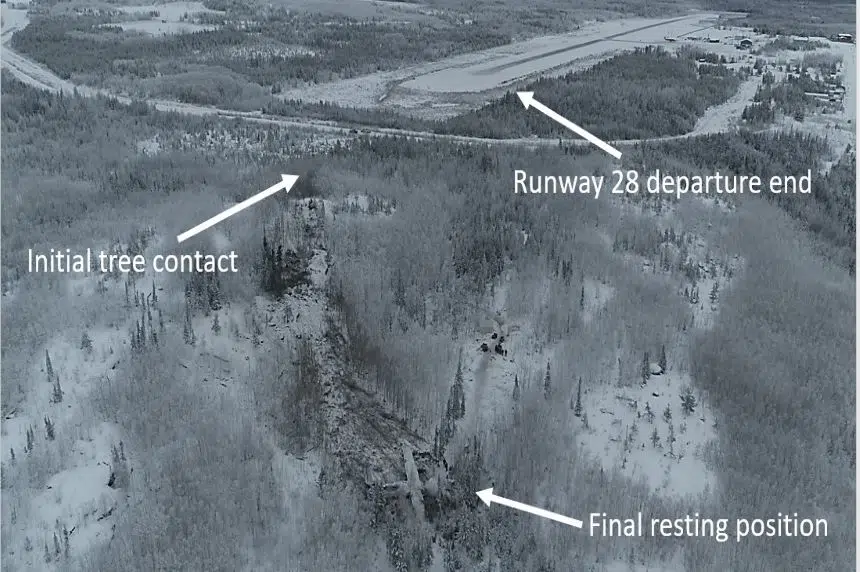

About 30 seconds after takeoff, the plane rolled to the left, the pilot tried to correct it, and the craft came down. According to the report, the fuselage of the plane wasn’t designed to take the type of impact it did, and the floor partially collapsed, while one wing also ended up in the cabin.

Every one of the passengers and crew members on board were injured. Nine passengers and one crew member were seriously hurt.

It took at least 20 minutes for 17 of the 22 passengers to get out of the plane, and another three hours to extricate one passenger. Several passengers suffered major head, leg and body trauma and a 19-year-old man ultimately died of his injuries nearly two weeks later.

Fox said early in the investigation it became clear that investigators needed to assess the risks of operating in northern climates and the risks of taking off in a plane with ice on it. The board did a survey of 650 pilots across the country in the summer after the crash.

Seventy-four per cent of those surveyed said in the past five years, they had seen planes take off with “contaminated surfaces,” and 40 per cent said they had “rarely if never” had access to de-icing equipment. That, said Fox, poses a high risk to transportation safety.

“That’s a systemic problem that has to be addressed,” Fox added.

In 2018, the TSB made two recommendations. The first was for Transport Canada to collaborate with airport authorities and operators on an urgent basis to make sure remote airports had the ability to de-ice planes. The second was to enforce that aircraft should never take off with ice on the planes.

It’s not clear whether Transport Canada has entirely implemented the recommendations, but it has shown “satisfactory intent.”

Fox says it’s up to airline operators to have the equipment they need, and passengers can also ask what actions they take. They can question the airport authority as well.

Since the crash, the Fond-du-Lac airport has received de-icing equipment necessary to service planes taking off, and $12 million was allotted in 2019 for upgrades to the runway, one taxiway, and the tarmac.