Tom Renney remembers exactly where he was during the attacks of Sept. 11, 2001.

It was the first time the New York Rangers had ever held their training camp in Manhattan. Renney, who was entering his second season as the team’s director of player personnel, was at Madison Square Garden as players checked in for their physicals when the first plane struck the World Trade Centre.

The spectre of 9/11 still haunted New York City four years later when Renney began his first training camp as the Rangers’ head coach. Sensing that the Rangers could be a rallying point for a hurting city, Renney told his team that they had to play the 2005-06 season for the fans.

“You know what? We owe this city and we owe the New York Rangers fans everything we have,” Renney recalls. “This is not about hockey, this is about allowing a city that supports us like nobody else the chance to feel good, and feel like there’s a rebound and feel like there’s something that they can feel good about.

“I said, that is our responsibility and our obligation to the Rangers fan. And quite honestly, you know, the National Hockey League.”

That season the Rangers became the first team to do a post-game stick salute to thank their fans, a practice that is now common around the NHL. Renney led the team to a third-place finish in the Atlantic Division and New York’s first playoff berth since 1997.

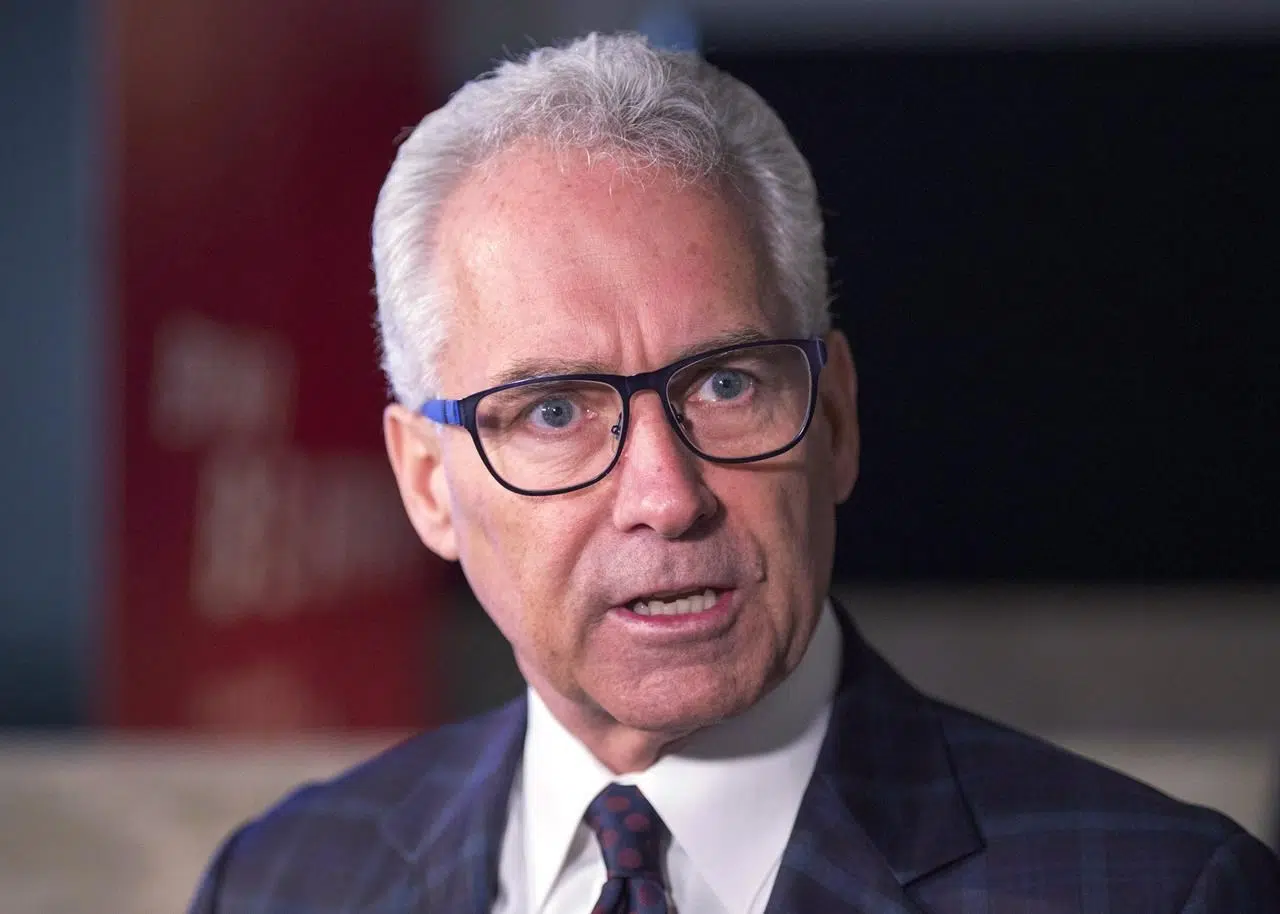

Renney is now the chief executive officer for Hockey Canada and although he doesn’t know when professional or amateur sports will return, he says that like his time with the Rangers, they will play a critical role in healing the country when the COVID-19 pandemic ends.

“I believe Canadians are very resilient people. I think the hockey community is a resilient group, not just those that play it, but those that love watching it,” said Renney. “When the time is right, I think our participants and volunteers across the country will relish the role in leading Canada back to normal.”

Hockey, like all elite sports, is on hold as officials do their bit to help stop the spread of the COVID-19 virus. The NHL has paused its season and the Memorial Cup, Canada’s national major junior championship, was cancelled along with the Canadian Hockey League’s playoffs.

There’s no telling when the NHL, NBA, Major League Baseball, CFL or any other professional sport will return. But like Renney, Golf Canada CEO Laurence Applebaum says his sport will be ready to unite Canadians when restrictions on public gatherings are lifted.

Also like Renney, Applebaum has seen firsthand how sports can bring a community together after a tragedy.

Applebaum was the vice president of Salomon Canada, a sports equipment manufacturer, a decade ago and was in Vancouver for the 2010 Winter Olympics. He remembers a literal and figurative cloud hovering over Vancouver after Georgian luger Nodar Kumaritashvili was killed during a training run hours before the Games opening ceremony.

“The sport community came together to mourn him and the weather changed and it ended up evolving into an incredible celebration of sport and humankind coming together,” said Applebaum. “So my prevailing theory is the sun will rise again (when the pandemic is over).

“And golf, golf will rise again and return to being an incredible part of our lives. It’s just going to take some time.”

Bruce Kidd, a historian and professor at the University of Toronto, believes that sports are in a unique position to help rally cities or countries after disasters because people can identify with the athletes. That power will become even more apparent when normalcy returns after the novel coronavirus pandemic is over.

“I think to which athletes and coaches’ lives have been thrown into complete disarray is something that most people can identify with right now,” said Kidd, who competed for Canada at the 1964 Olympics and was twice named The Canadian Press athlete of the year.

Kidd, who likened the current public health emergency to the Spanish influenza pandemic of 1918-20, says that when sports return it will be cathartic for all of society because it will be a celebration of overcoming adversity.

“It will be a relief, it will signal a return to some kind of normalcy,” said Kidd. “It’ll be an opportunity for people to take control of their lives again, whether it’s participating in sports or watching them.

“Psychologically, it will be empowering and I think that’s really important.”

John Chidley-Hill, The Canadian Press