Public health officials across Canada and around the world are working flat out to test as many people as possible for the novel coronavirus.

Srinivas Murthy is working to figure out how to help them if the result is positive.

“What medicines work?” he asks. “We don’t know.”

Murthy, a professor of critical care at the University of British Columbia, is one of hundreds of Canadian scientists spending long hours in their labs and by their computers trying to help governments and clinicians figure out how to deal with the COVID-19 pandemic.

Earlier this month, the federal government awarded almost $27 million in grants to coronavirus-related research. The money is funding 47 projects across the country.

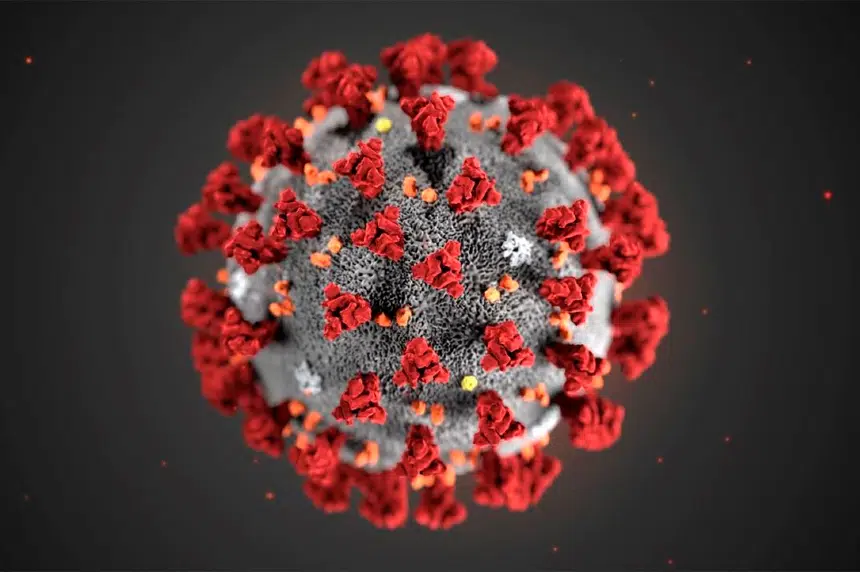

There are studies into faster diagnostic tests, how the disease is transmitted and the structure of the virus itself. Other scientists are considering why some people ignore public health warnings and how the public perceives risk.

Some are asking how to keep health workers safe. Some are looking at the effects on children or Indigenous people or on food security. Lessons from past public-health crises are also being studied.

“It’s basic research. It’s public health research. It’s community-based research,” said Yoav Keynan of the National Collaborating Centre for Infectious Diseases at the University of Manitoba.

“Many are redirecting their efforts to the virus. There are many things that need to be worked on.”

Murthy is trying to find out how hospitals can treat patients who have the COVID-19 virus. Each virus is different, he said, and what works on one won’t work on another.

“This is a new virus,” he said. “We don’t know what specific medication works.”

That means trying familiar drugs that have been effective on other viruses. Using what’s known about this coronavirus, Murthy estimates the chances of old drugs working on it and starts with the most likely candidate.

“We build on what we’ve already got,” he said.

Right now, he’s working with an antiviral agent that was originally developed in the fight against AIDS. Clinical trials with COVID-19 patients who have agreed to participate are the next step.

“We know it’s safe,” said Murthy. “We don’t know if it’s effective.”

When you include public health and medical personnel involved, the scientific fight against the coronavirus now involves thousands of people, Keynan said.

“There are many gaps in understanding the transmission of the virus — how long the virus stays on surfaces or the proportion of individuals that contract the virus but remain asymptomatic and serve as a reservoir for spreading the virus.”

The good news is that public-health research has come a long way since the SARS virus swept through 26 countries in 2003.

“We have better communication, better knowledge-sharing and better lab capacity,” said Keynan.

“Sharing of information globally and within Canada has improved dramatically over the last 17 years. And we’re going to need all of it.”

Canadian scientists are at the forefront of worldwide efforts to bend the curve of COVID-19 infections down, said Keynan.

“Canadian researchers are global leaders in infectious diseases and virology and we have better capacity than we had in 2003 to be meaningful contributors. We are making contributions.”

But no single lab or nation is going to come up with all the answers on its own, Keynan said.

“This is not a Canadian effort. This is a global effort.”

This report by The Canadian Press was first published March 22, 2020

— Follow Bob Weber on Twitter at @row1960

Bob Weber, The Canadian Press