Election season is here, and the time for door-knocking, lawn signs and regular doses of polling data begins.

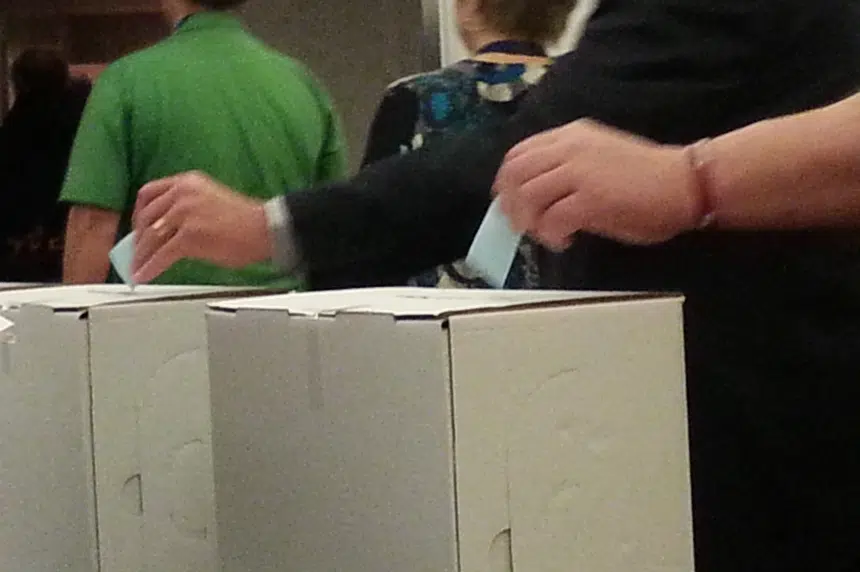

Voters across Canada will head to the polls on Oct. 21 to choose which party forms government, whether that’s the incumbent Liberals, the Conservative Party, the NDP, the Green Party or the People’s Party of Canada.

University of Regina political science professor Jim Farney said that unlike the 2015 federal election, this year’s race really consists of “two races.”

“We’ve got the Liberals and we’ve got the Tories competing for first place nationally,” Farney told John Gormley on Wednesday. “And then we’ve got this really interesting slugfest, I think, between the Greens and the NDP for who’s going to be the third party in Parliament.”

That should play out on a riding-by-riding basis, because the Greens and the NDP “are so close,” Farney predicted.

“I like it when campaigns matter. I think what we see in the next 40 days from the leaders is going to smooth people back and forth between those two columns a lot,” he said.

Vote-splitting is an outcome that parties should watch out for on the left and on the right, Farney said.

He cited numbers that show about 60 per cent of Canadian voters identify as progressive, meaning that in tight ridings, they’re apt to be torn between choosing the Liberals, the NDP or the Greens.

Former NDP MP Erin Weir’s riding of Regina-Lewvan is a good example of that, Farney said.

But he added that the Conservatives should keep an eye on Maxime Bernier and the newly formed People’s Party of Canada.

“It’s possible that if they pull three of four per cent of the right flank of the Conservatives in those 905 ridings around Toronto, that might be enough to throw (the election) to the Liberals,” said Farney, referring to the area code in that region. “This vote-splitting thing really ends up mattering at the end of an election.”

Another aspect that makes predicting election outcomes difficult is that younger voters tend not to stick to the same party they vote for election over election, he said.

In Farney’s view, a key to election victory has less to do with luring voters over from one side of the spectrum to the other, and more to do with getting a party’s base out to vote on election day.

“It’s making sure that your supporters turn out to vote. That was really the Stephen Harper secret of campaigning; the Conservatives polled in the mid-30s, high-30s in 2011, but those people came out and they voted,” Farney said. “Turnout is hard to predict.”

An example he gave was that large numbers of Indigenous voters showed up on election day in 2015 to cast their ballots “mostly we think” for the Liberals.

“There are some ridings like Desenethé-Missinippi-Churchhill River (in northern Saskatchewan) where that will really matter. But we don’t know if those folks will come out again,” he said.