On the 80th anniversary of Bergen-Belsen’s liberation, we continue the extraordinary tale of Klara Belkin’s life.

At just 15 years old, Klara’s world was shaken and irrevocably changed by the horrors of the Holocaust.

She arrived at the Nazi concentration camp of Bergen-Belsen, where she would endure five months of unimaginable suffering. But unlike so many others, Klara survived.

In this episode, the 95-year-old recounts the brutal reality of life in the camp — the overcrowding, the starvation and the constant proximity to death.

She also reflects on the quiet moments of humanity that offered brief glimpses of hope, even amidst the horror.

Klara’s story within the camp is a testament to the power of survival and a reminder that even in the darkest times, the human spirit can endure.

Listen to part 2:

Listen to part 1:

If you were to walk past Klara Belkin on any Saskatoon street, you would never guess that she is someone who has witnessed the worst that humanity has to offer. She has a great smile. She’s quick to brag that, even at 95, she doesn’t have dentures. Those pearly whites are all hers. (Brittany Caffet/650 CKOM)

Transcript of Episode 2:

At 95 years old, Klara Belkin has seen a world transformed — from the atrocities of war to quiet moments of peace.

She’s lived through a nightmare that most of us can only imagine, and yet here she sits, with a kind smile and a quiet dignity.

And now, with the clarity that comes only with age, she tells her story — not to dwell on the past, but to ensure that we remember it.

Klara: “They took us into a shower. A room with a shower, big, big. We were told that was the gas chamber.”

By the time 15-year-old Klara arrived at the Nazi concentration camp of Bergen-Belsen, there were 60,000 other men, women and children crammed into overcrowded barracks.

Klara: “Everybody slept in, you know, a bed on top of each other. But the problem was people were dying on top of you too.”

For five long months, Klara and her family waited. Waited for food, waited for relief, for rescue… for their own bodies to betray them.

Klara: “You just stand there because you had no energy, and you had nothing else to talk. You’re not the same anymore. Because if you would be the same, I think you would go crazy. You become, I use that word I said, numb. You completely numb. You accept everything. It becomes natural. It’s hard to believe. The way we are now, physically and mentally, we would, you know, scream. But somehow, you know, it’s just almost like a mental change, completely. You’re not the same person anymore. I just put it that way. You’re not the same.”

The true horror doesn’t only lie in what they endured, but in the unthinkable things they had to witness.

Klara: “They brought in thousands of Russian prisoners, the Germans. And they were young men, but they looked old. They are just completely emaciated, and they had to stand out. They weren’t in the barracks. In their section, they were standing outside with this outfit, this striped thing, until they dropped dead. Understand? In two weeks, they was all gone. Thousands. And I saw them. They was standing there, and they just dropped. And then every evening, they came with other poor souls, you know, pushing this cart, throw the bodies up on the cart, you know, and put them away. And that was just every day so natural that, you know, you almost don’t even feel anything. It’s natural.”

But somehow, humanity prevailed.

Klara’s apartment is scattered with caricatures she’s drawn. She has a knack for capturing the essence of those around her with a few quick strokes of her pencil. These drawings add a touch of humour and lightness to the space she now calls home. Klara has a way of infusing joy into everything, even in the smallest details of her everyday life, a remarkable quality when you consider the horrors that she has survived. (Brittany Caffet/650 CKOM)

There were small, heartbreaking glimpses of the innocence of childhood that couldn’t be erased, even in such a brutal place.

Klara: There was a little girl, must have been about three years old, two or three years old. Had a doll. This is one I’ll never forget. A little doll. You see, every morning we were full of lice, and her mother was cleaning her up from the lice. They take off the dress, they turn it inside out. And, you know, in the crevices, full of lice every morning. So they got killed. The little girl sits with her doll, and in Hungarian, lice is tetvek (sp?). I said to her once says, Suji, what are you doing? ‘Tetvek sack! (sp?)’ Her mother was getting rid of the lice on her body and her clothes, the little girl clothes, so she was doing with her doll.

It was these fragments of humanity that kept them going.

And in the spring of 1945, the people confined within the walls of Bergen-Belsen felt a strange shift in the winds of war.

On April 7th, as the war was nearing its end, thousands of Bergen-Belsen’s captives were loaded onto yet another cattle car, headed for Theresienstadt – another concentration camp. Klara Belkin was among them.

Klara: This is something you can’t imagine. And it’s very hard to believe that that human being can do this to others.

After six days in that cattle car, something miraculous happened.

Klara: Well it was very interesting, because before that, you see, we heard there was fighting there. There was war. And then suddenly was quiet, nothing, quiet, no, nothing.

On April 13, 1945, the train screeched to a halt.

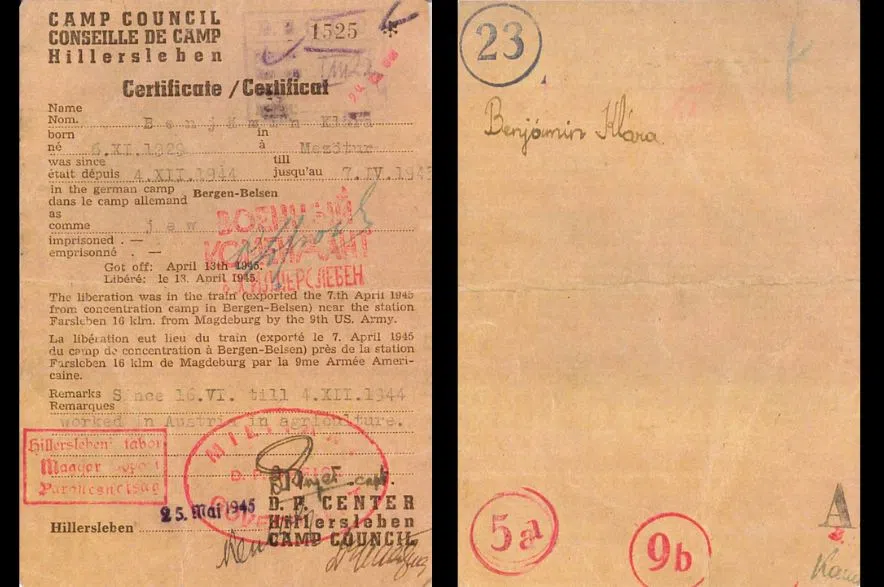

Klara Belkin has kept many of her documents from WWII. She still recalls watching soldiers stamp this pass that showed she had been liberated. (Submitted)

American forces had intercepted the death train.

Klara: The Americans saw there was a train, long train in the valley. They wanted to know what’s in it, maybe ammunition or soldiers or something. And so they came. I’ll never forget that soldier, when they opened that thing, he looked at into, into that cattle car, and he was just looking because they didn’t expect that. They never knew about this.

The joy, the overwhelming relief of seeing the Americans — those soldiers who would deliver them from hell — was something Klara would never forget.

Klara: That was our freedom. That was it. It was like a dream, you know.

In this 2010 photograph Klara and her husband Emile Belkin are pictured with Frank Towers and Carrol Walsh, members of the 30th Infantry Division. They were part of the team that liberated Klara on April 13, 1945. Belkin said the reunion was incredibly emotional. (Submitted)

And though Klara was free from the hands of the Nazis, her fight for freedom wasn’t over yet.

Tomorrow, in the final chapter of Klara’s remarkable story, you’ll learn of Klara’s journey out of Hungary and the life she built for herself right here in Canada.

In Saskatoon, I’m Brittany Caffet.