Today marks 108 years since the Canadian Corps attacked Vimy Ridge, marking the first time all four Canadian divisions fought together as a cohesive unit. Nearly 3,600 Canadian soldiers died and about 7,000 were wounded. Tamara Cherry welcomes Tim Cook, chief historian and director of research for the Canadian War Museum, to remember this notable day in Canadian history.

Listen to Tim Cook, chief historian and director of research for the Canadian War Museum:

Tamara Cherry: Can you tell me about the months of preparation in this battle?

TIM COOK: The preparation was essential, and the Canadians had been learning in the terrible environment of the Western frontier. Listeners may remember the Great War, the First World War. We were only a country of 8 million people, but we had 600,000 soldiers in uniform.

By the time of Vimy, we had those four divisions you mentioned, Canadians from across the country. They were there staring up at this impossibly large Ridge, seven kilometers long, commanding the height where the Canadians were below them.

They had to prepare for this and so they raided the enemy lines. They honed their artillery tactics. They engaged in a new counter battery work, which was to in effect knock out the German guns. They used aerial intelligence, and all the while, they trained for this brutal battle that they knew would come on the 9th of April 1917.

What did the more than 15,000 Canadian soldiers face when they arrived?

COOK: This was early April, but the Canadians had been on the front since late 1916 when they had limped off the Somme where they had suffered 24,000 casualties and about two and a half months of attritional warfare.

They’re in the mud and the muck, it’s freezing cold. I have spent years reading the letters and diaries of those Canadians who have served there. They’re preserved in archives and museums, and they’re in the in the homes, cherished by the families many generations later, and people have shared those with me.

Those young guys were writing about facing down their mortality. They knew that that there was a good chance they would be killed or maimed in the attack.

Fifteen thousand went forward at 5:30 a.m. in the first series of waves. They were supported by another 10,000 behind them.

It was over this incredibly large front, brutal fighting German machine gun positions cutting down the Canadians as they advanced forward.

On that day, incredible skill and courage that I think you and I would have a hard time imagining allowed the Canadians to claw their way up that ridge, and in some places, down the ridge.

By the end of the day, we had captured most of the ridge. Over the next three days, until the 12th of April, it was finally in Canadian hands, but it came at a terrible cost in lives, with 10,600 Canadians killed or wounded in those four days.

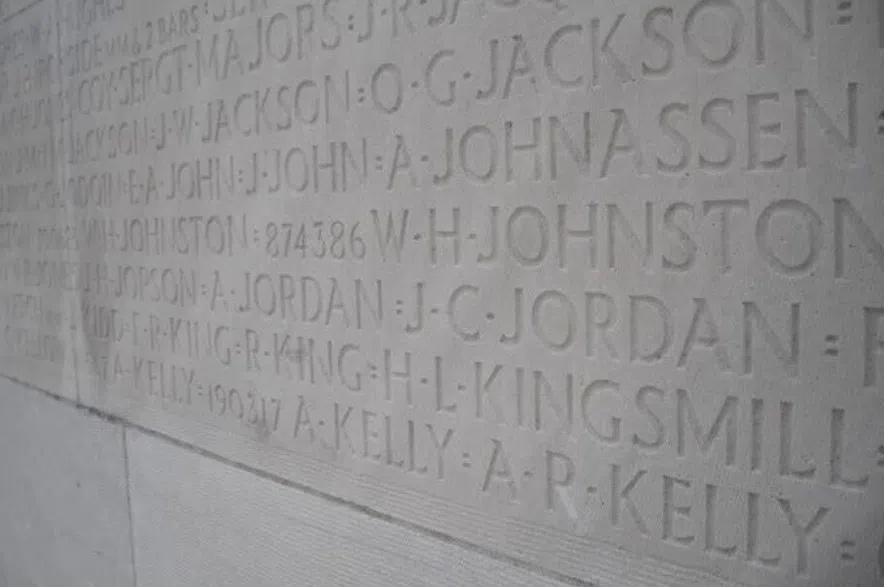

Carved on the walls of Canada’s National Memorial are the names of 11,285 Canadian soldiers who died in France but whose bodies were unidentified or unrecovered at the time. (Céline Grimard/650 CKOM)

What does the Battle of Vimy Ridge represent for Canada in your eyes?

COOK: Vimy is an important martial symbol for Canadians. We don’t often think of ourselves as a military people, but that’s a bit odd when we fought in the two World Wars, the South African war, the Korean War and the Cold War, which defined a generation.

Most recently, in Afghanistan and the ongoing defense of North America with the United States, NATO commitment, peacekeeping, it goes on and on.

We are a country that has been shaped by war. Vimy is perhaps our most important symbol because of the battle that was fought there, but also because we built our monument there.

Listeners will remember the monument was unveiled in 1936 and it’s still there. It’s a very powerful site of memory and of mourning. Canadians have been traveling there for multiple generations. It is a place where one feels very Canadian.

It is a place of conflicting emotions, grief and sorrow, but also that pride in country. All of those things have come together. And I wrote a book on Vimy called Vimy: The Battle and the Legend. The legend part is important because this is an important symbol for Canadians. In this day and age, when our own sovereignty is under threat. Vimy seems to be one of those powerful, emotive and evocative symbols or legends that continues to resonate and pulse with Canadians.

There have been increasing talks of a unity crisis by current and former leaders. Are you thinking about this day differently this year than in previous years?

COOK: One of the interesting things about Vimy, or other important symbols we have in this country, is they are both grounded in the past. They are historical events, but they also reflect the times in which we live.

Some of your listeners may remember 2017; that was the 100th anniversary of Vimy. 25,000 Canadians converged at Vimy Ridge, the monument. It was a powerful day of celebration and commemoration.

Eight years later, we have a different threat. We are looking to our history to think of the things that keep us bound together. We’re an impossibly big country. We have many different regions, and yet it’s our history that often brings us together.

It is at our own peril, I would argue that we fail to teach this history properly, that we diminish it, either through apathy or neglect, and it is a continual fight to ensure the history matters and this generation and those that follow have a proper understanding of the important and hard and sometimes great things that we have done together as a country.

The preserved trenches found at Vimy – only a small portion of the network of trenches that ran the entire length of the Canadian sector – were reconstructed in the same positions as the Canadian and German outpost lines in 1917. At some locations, these trenches are only 25 metres apart. (Céline Grimard/650 CKOM)

Do we do a good enough job teaching our kids about Vimy Ridge?

COOK: It’s an eternal challenge for Canadians to know their history. I’m very lucky at the Canadian War Museum to have worked there for years. We, of course, tell the story of Vimy through artifacts and incredible oral histories and photographs in our museum.

I’ve met teachers across this country who teach and talk about this history, but not all of them do. I get asked this question a lot I’m deeply biased to having devoted years of my adult life to this.

It’s impossible to quantify, except to say that, yes, there are many Canadians who don’t know about Vimy or what we did at Juno Beach on the sixth of June 1944 or the other important events not linked to our military that define us as Canadians. So yes, we have to work on this.

We live in a globalized world. There isn’t much that is uniquely Canadian now, you can say hockey and Tim Hortons and a few other things, maybe. Even those can be Americanized, but our history is our own.

This is our story, and don’t expect the Americans, the British, the French, or anyone else to tell our story. That’s up to us.

This is a good day, perhaps, to reflect upon and to bear witness to that service and sacrifice 108 years ago.

We’re seeing a rewriting of history in the United States, with President Donald Trump signing an executive order recently for, quote, restoring truth and sanity to American history by eliminating what he considers, quote, anti-American ideology from the Smithsonian Institute. As a historian, I wonder how you’re reflecting on that and what lessons we should be taking from our neighbors to the south regarding the protection of our own history.

COOK: That order and others like it are deeply disturbing, and they should be disturbing to anyone.

We shouldn’t be naive and think there is a constant battle that goes on in interpreting the past, and that’s that’s fair, that’s good. Democratic societies have these discussions. They are important. They allow us to test assumptions and to think about the past in new ways as it reverberates in the present.

We can’t censor or banish the stories that make us uncomfortable. We have to address the past with truth.

There would be few who would disagree with that. The devil is probably in the details. There may be some who say we have taken a two negative view of the past, that we focus too often on atrocities and loss and diminishment of civil liberties, those are fair discussions to have.

If we slip into the Orwellian 1984 world of rewriting the past to suit the present. We will go down a dangerous road.