In the heart of Saskatchewan, where the prairie stretches endlessly beneath a wide open sky, the community of Tokyo once stood.

For Brousse Flammand, Tokyo was home. The story of this place is not just one of a town, but of the people who lived there: the Michif.

“We were a mix of people. We refer to ourselves traditionally as Michif,” Flammand said in an interview with 650 CKOM.

“Even when the white man was calling us half-breeds, we knew ourselves as Michif.”

It was not a term of shame, but one of identity, of belonging. “That’s who we are as a people. Our language is Michif. We have common culture. We have common language. We have a common history, and, most importantly, Michif have a common consciousness. In other words, we have a common world view.”

Flammand was raised in a world where Michif was the heartbeat of daily life. It was the sole language he spoke in his early years, only encountering English when he started school at six years old.

“The Michif language is made up of Plains Cree verbs,” he explained. “It’s not Woodlands Cree or Swampy Cree. It’s Plains Cree, as well as French.”

But like the community he grew up in, the language of his youth is slipping away.

Michif is now classified as ‘critically endangered’ by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), with only a handful of speakers left to pass it on.

Listen to Brousse Flammand on Meeting Ground:

Life in Tokyo, Saskatchewan

“Tokyo was a very vibrant community when I grew up. Was born and raised there. We had our own school, we had our own stores, we had our own church, we had our own community,” Flammand recalled fondly.

Tokyo sat 12 miles south of Yorkton. Now known as Crescent Lake, the name Tokyo was never meant to be permanent. It was a nickname, born out of a moment of humour from Flammand’s uncle.

“He came back from a war, and laughingly referred to it as Tokyo,” he said with a laugh. “Name caught on, and few generations later, we still think of it as Tokyo.”

Flammand said Tokyo, with its small but proud population, was a place where neighbours watched over one another and where the notion of community was all-encompassing.

“We had no police. We didn’t need police. We had no judges, no jails, no teachers, no bouncers, no game wardens, no authority, if you will. But yet we were very, very strict on our own laws.” Flammand said, recalling the values of respect, honesty and self-sufficiency that governed daily life.

“You weren’t a bully, and you made sure you stuck up for people that needed sticking up for. You made sure you provided for your family and for those around you that were less fortunate.”

“We didn’t lock our doors. We had no thieves in Tokyo… because of who we were and how proud we were of our surnames. I’m a proud Flammand,” he said with a glimmer of that pride still shining in his aged eyes.

Like all children, Flammand grew up knowing only the world around him. He recalled, “I didn’t know I was poor until I left Tokyo.”

He didn’t know it because his family didn’t have to buy much. The community lived off the land — gardens that thrived in the fertile soil, animals that fed families and the spirit of self-reliance that marked every aspect of daily life.

“We had a huge garden, and we could live off that all summer if we wanted, which we did,” he said. “We had no power bills, no water bills, no rent. We had no bills, period.”

But that was Tokyo in its prime. The comfortable life that Flammand’s family and many others had built on this land was slowly chipped away as time went on. By 1965, Tokyo was gone.

“Tokyo may have been the last Michif community to have been dispersed,” Flammand noted. “They’d move a family out, and as the family was moved out they’d burn the house, until there was nobody left.”

Now, Tokyo is a memory. A place that exists only in stories and the minds of those who remember the sound of its name and the language of its people.

“About 30 of us still speak it. It’s still an oral language, meaning, when us 30 die, the language dies,” Flammand said, referring to the number of fluent speakers.

According to Statistics Canada, in 2021, 1,485 people reported being able to have a conversation in Michif. The Government of Canada has acknowledged that the language is critically endangered.

“When the language dies, so does this culture,” Flammand said grimly.

A race against time: Flammand’s fight to preserve Michif

Flammand views the loss of the language as a loss of more than just words. It’s the loss of a worldview, a way of living that is slipping through the cracks of time.

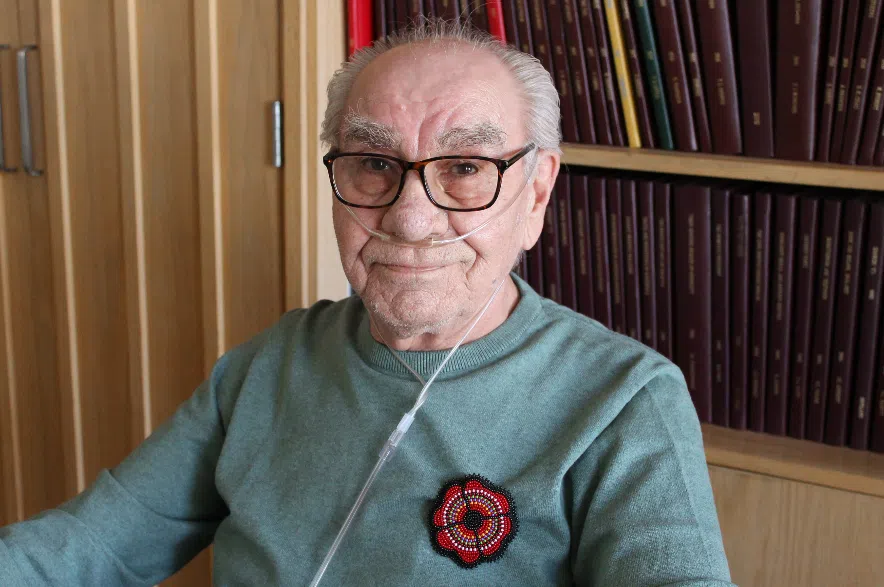

But he hasn’t given up. At 80 years old, he continues the work of preservation, hoping that his efforts will leave a legacy for the next generation.

“I’ve accumulated a lot of Michif resources and provided a lot of Michif resources, some of it being audio,” he said. “I’ve been teaching certain people now so that if I could, before I die — and that’s not too long from now — we’re almost there now that they could now take the language and teach it.”

It’s a race against time. But it’s a race that Flammand is determined to win.

Brousse discusses the terms Métis and Michif on YouTube

“It’s up to me now to leave as much as possible for the next generation,” he said. “When I’m gone… Well, at least I would have done my part. That’s what keeps me going today.”

Flammand is actively working to pass on his knowledge. As the president of the Michif Speakers Association, he leads language programs and creates educational resources, including early learning curricula and online lessons.

He has worked alongside researchers to document the language, his tireless efforts a reflection of his deep-rooted connection to his heritage.

Though more than six decades have passed since he last walked through Tokyo, Flammand still feels a longing for the community that once thrived.

Yet, every now and then, a fleeting moment brings him back to those days.

“Not very long ago, we were visiting Michifs, real Michifs in the Turtle Mountain Reservation. She’s 96 or 94 and her husband is in the 90s,” he recounted. “Sunday morning they cook this breakfast, and I had another friend of mine come play the fiddle there. And there we were. Sunday morning, two stepping around in the kitchen. Now, how Michif is that?”

Though Tokyo may be gone, the spirit of the Michif people endures in the language, in the memories and in the communities that continue to gather.

“Tokyo is not there, but the spirit is still there,” Flammand said.

And for Brousse Flammand, that spirit is something worth fighting for.

His work and dedication are keeping Tokyo alive, one Michif word at a time.