By Teena Monteleone

They are hidden pieces of history scattered throughout Saskatchewan.

Fallout shelters, also known as fallout reporting posts (FRPs), were built during the Cold War to thwart the effects of a nuclear attack on the country. Dr. Andrew Burtch, a military historian, has mapped as many of the remaining underground bunkers as he can find.

“People would build fallout shelters in their backyard and in their homes, and that was largely a voluntary effort that citizens were urged to do, especially following about 1959 as the threat of intercontinental ballistic missiles came about,” Burtch said.

READ MORE:

- From Fairyland to prairieland: war brides recognized in Sask.

- Sask. man’s Victoria Cross finds permanent home in Ottawa

- ‘Contributing to a legacy:’ Campaign underway to honour Regina Rifles on Juno Beach

“An attack could come with very little warning anywhere across the country, and so you needed some way to get underground and distance yourself from the radiation for that period, during which it could be lethal.”

The Diefenbunker is perhaps the most notorious fallout shelter in Canada. The four-storey, 100,000-square-foot underground bunker was built between 1959 and 1961 to protect the country’s top officials in the event of a nuclear attack. Once top secret, it is now a museum and national historic site.

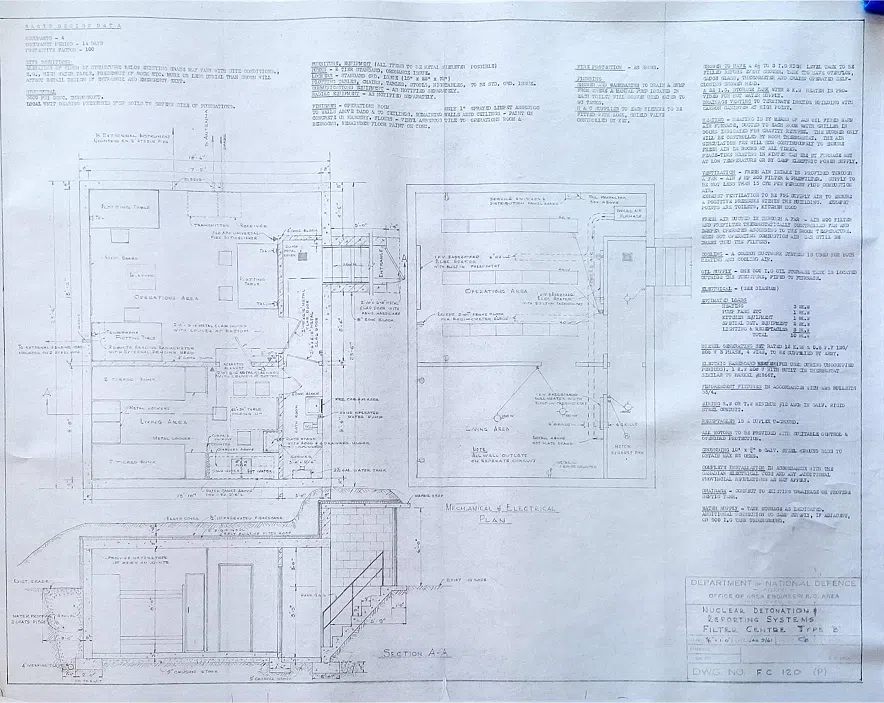

Official plans for a filter centre, or one of the larger fallout shelters used to gather messages from the various smaller shelters and transfer them on to provincial and federal authorities. (Submitted photo/Andrew Burtch)

Burtch said the government established a network of about 1,500 FRPs across the country. They were built by contractors working with the Canadian Army, using mostly existing federal, provincial or municipal buildings that could easily be built upon or expanded.

“Things like Canadian Pacific rail stations or Canadian National rail stations, RCMP or provincial police offices, forestry offices…anywhere where there could be essentially some land that they didn’t have to work with a private homeowner who could rescind the arrangement,” he said.

Burtch, a historian at the Canada War Museum, identified the locations on a map.

Burtch said the idea is that the grid of fallout shelters would be staffed by volunteers during a nuclear war. Saskatchewan wasn’t likely to be targeted directly by Soviets, as it didn’t have a sizeable military base or industrial target, and was primarily agricultural. The concern, however, was the lingering aftereffects of an atomic bomb that could be carried by the wind hundreds of kilometres away.

“They would use a Geiger counter to go outside and say whether radiation was falling or increasing, and then they would be able to report that through radio or some other form of communication to people who were sheltering in place, including ordinary citizens.”

Burtch said it’s unlikely the bunkers were ever used during a legitimate threat. The biggest scare, he said, would have been the Cuban Missile Crisis in October, 1962, when the United States and Soviet Union came close to nuclear conflict.

“Some may have been staffed just for the purposes of exercises, just to see if phones or communications were working the way they’re supposed to. And some of these were nationally broadcast like in November of 1961 – there was a national broadcast called Tocsin B,” Burtch explained.

Exercise Tocsin B was a nationwide nuclear preparedness drill that lasted 24 hours in November of 1961. It was the largest civil defence drill ever held in Canada.

More than 100 fallout shelters were built in Saskatchewan between 1961 and 1963. The bunker in Dorintosh was beneath the Natural Resources building. At Imperial, the bunker was located downstairs in the RCMP detachment. Gronlid had its buried shelter located next to the CP station. Each were equipped with a bed and supplies, but the key was the connection by radio, telephone or even telegraph to central bases.

paNOW was unable to source any photos of Saskatchewan fallout shelters prior to publication, but the Manitoba Historical Society shared some from bunkers that were uncovered the last few years.

Burtch said today there is a fairly small network of people who even know about the fallout shelters.

“You really had to know where they were. They would just look like a cinder-block house from the outside, or maybe just a stairwell or a hatch,” he said.

The shelters didn’t have the presence of other Cold War infrastructure like air raid sirens, which were visible on posts and sounded from time to time, creating an audible memory.

“I think it’s fair to say that they’re forgotten about, or at least a little-known element of the Cold War infrastructure that was created to respond to this impossible problem of how to respond to nuclear weapons,” he said.

Maintenance of the bunkers stopped in the ‘60s and ‘70s. Some were abandoned in the midst of being built, because of financial changes.

Burtch made the map of fallout shelters as part of a broader project he was doing about civil defence. With help from volunteers, he was able to map out some of the remaining sites, although he said it’s very much a work in progress, and isn’t guaranteed to be 100 per cent accurate.

“There may be more out there that people don’t even realize are fallout shelters, because they were repurposed as a cold cellar. They were meant to be unobtrusive,” he said.

Burtch cautioned anyone who searches for the bunkers or finds one to be careful, since most would not have been maintained and may have mold or other safety issues.

As to whether they could work today if there was a nuclear threat, Burtch guessed they’d help keep people alive… for a period.

“But as with the broader question of the logic of civil defence during the Cold War is that question that everyone had, which was ‘What happens when you leave?’” said Burtch.

“You would be emerging to a truly unknown landscape, and one that you know would be considerably more hazardous to your health than previously. So yes, it would help you get through an emergency, but whether it would actually help you survive nuclear war, that’s a question that I’m very grateful that we never had to answer during the Cold War… and I hope never to really contemplate in real life.”