A handful of open grave sites covered Warman Fire and Rescue’s training land Thursday morning, just beyond Saskatoon’s city limits.

Inside the holes were plastic human bones, clothing, shell casings and more, scattered, waiting for discovery by a team of investigators assembled from across the country.

The imitation remains and their excavation were part of a course on forensic identification and forensic anthropology.

Dr. Ernie Walker, an RCMP special constable and forensic expert, has been teaching it for decades.

The purpose, he said, is to instruct law enforcement personnel on locating, recovering and identifying human remains. Investigators taking part spend a few days in the classroom focusing on anatomy and techniques before heading into the field to combine their knowledge with outdoor experience in the field.

Walker said he’s taught forensic topics from grave excavations to examining burned remains.

“I think the reputation of this course has certainly expanded,” Walker said, noting the course was created in Saskatchewan.

“It’s a monster class to put together,” he said. “There are a million details.”

Walker said investigators were working with surface scatters on Wednesday — simulating human remains that were deposited and then scattered around an area by animals.

Dr. Ernie Walker is a special constable with the RCMP and a forensic expert who also assists municipal forces as part of his forensic anthropological work. (Libby Giesbrecht/650 CKOM)

“They had to delineate a crime scene,” Walker explained.

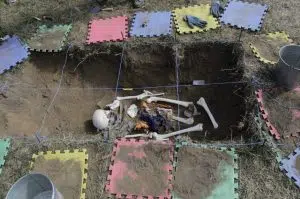

Thursday morning’s excavation of a simulated clandestine grave made investigators learn how to establish the location of a grave and then process the scene.

Walker said it’s careful, scientific work, and reflects what would happen at a real crime scene.

“I’ve worked almost every missing and murdered woman in the province,” Walker said.

Walker’s resume includes investigations like Robert Pickton’s farm, missing women in Saskatchewan and Alberta, and Saskatchewan serial killer John Martin Crawford.

“Anytime there are remains that cannot be identified by just looking at them, it’s typically my file,” he said.

That can include fires, car wrecks, bodies found in water and skeletal remains, in addition to homicide cases.

A lot of his time can simply be spent assessing whether a bone is human or animal in order to assist law enforcement. Walker said he does this for police forces across the country.

Once remains are located and recovered, an assessment and identification process begins, with the anthropologist trying to build a post-mortem profile of what information the set of remains might contain.

Walker has to determine things like sex, age at death, ancestry, pathologies or abnormalities, time of death, and ultimately provide a personal identification, if possible. Techniques like dental record comparison and DNA identification have progressed a long way, Walker said, and can be pivotal in these identifications.

But investigators also depend on the decomposition of remains — if someone’s teeth have been destroyed or there is no soft tissue left to extract a DNA sample from, those are not viable tools.

Fires can be the most difficult, Walker said, depending on how damaged a body is when he receives it.

The tasks can’t be completed overnight. RCMP Sgt. Donna Zawislak said the course participants started their digs around 8 a.m. on Thursday, only uncovering most of their shallow grave contents around early afternoon.

“If we want to do it right, we have to have a process in place; we can’t just go out there and dig things up,” said the sergeant, who works as part of the RCMP’s historical case unit in Saskatchewan.

That means starting at the top layer of soil on the ground and descending layer by layer, carefully going through dirt and debris to find clues, and documenting discoveries through photographs, notes and measurements, until they expose as much as possible and can capture a clear image.

In the simulation, things like clothes, bullet casings, empty cans and bottles, needles, cellphones and jewelry were included in the grave sites.

Walker said the goal is to make the course as realistic as possible.

“It’s all there,” he said. “It just doesn’t smell as bad as it normally smells.”

Searchers in the simulation not only had to excavate the clandestine graves, but first had to determine which of several possible areas might be the best to excavate.

A couple “red herring” graves were included in each area to force investigators to make use of probing equipment like metal detectors and ground-penetrating radar to determine the best place to use their resources.

“I’ve been involved in investigations where somebody kind of gave a ball-park … area of where something was, and then we had to hone in,” Zawislak said, comparing the training to real-life investigations she’s worked on.

Investigators had to ensure nothing was left behind in a grave once they’d excavated, checking for further remains or evidence that might be buried deep.

An excavated clandestine gravesite dug up by investigators taking the RCMP’s forensic anthropology course on Sept. 15, 2022, just outside of Warman, Sask. (Libby Giesbrecht/650 CKOM)

The course teaches investigators how to use old-school tools like sifters, used to find small pieces of evidence like bone and shell casings in the piles of dirt and rocks, as well as more modern technology like drones and ground-penetrating radar, which Walker said has been popularized in the recent discoveries of graves at residential school sites.

Walker said he likes to think that in Saskatchewan, police have stayed on top of those changes, especially in research.

Walker said experiments like putting pig carcasses in rivers with tracking devices attached have tried to predict where bodies in the water might end up. Studies examining markings on bones have used animal remains to see how certain instruments affect bones.

“We’re always thinking ahead,” he said.

Christian Rouleau, with the Quebec Provincial Police in Montreal, said he was grateful to have the opportunity to travel to Saskatchewan to take the forensic anthropology course.

“I was really pleased to come here,” Rouleau said. “It’s something we do a lot in our line of work.”

Rouleau said learning how to identify remains as belonging to an animal or a human was a skill he was able to hone during the course.

“I think it’s really, really good, and its going to help me a lot,” he said.

How officers leave a space behind can be just as important as the investigation itself.

After working to gather all the information and evidence, documenting each step and discovery, Zawislak said they try to return the property to the state they found it in, and make it a place families can return to quickly.

Russ Austin, chief of Warman Fire and Rescue, said planning for the course started back in May. Because of his department’s relationship with the RCMP — and the support he said the fire department often receives from the RCMP — Austin said it was a “no-brainer” to host the course for the RCMP on their training grounds just outside of Warman.

Austin said he’s worked several scenes with Walker in the past, saying “there’s no greater resource in the province for anthropology.”

He estimated between 50 and 60 people were on the grounds for the course, with people from across Canada and the U.S. taking part. Walker noted that a few coroners were present, as well as many law enforcement investigators.

With police work in investigations under constant scrutiny, Zawislak said the RCMP wants to see all investigations comply with the best practices.

“When we visit or go to a site, a clandestine grave, we are leaving our footprint there,” Zawislak said.

“We are aware of the environment, that there’s people driving by or family are watching. We’ve had family sit with lawn chairs and watch what we’re doing, so we want to do it in a professional and capable way that we are respectful to the family … plus the person that we are looking for.”

Zawislak said it’s also about uncovering evidence that is useful later in the investigation.

“It’s not just making sure we collect the evidence, but being able to use that information or that evidence,” she said.

The sergeant, who took the course herself in 2007, said best practices require resources — both equipment and officers. In the case of her unit, Zawislak said they are the only ones focusing on historical cases in the province, which requires her team to travel hours to various isolated communities in Saskatchewan, bringing those resources in tow.

“There are a lot of missing persons everywhere, including in Saskatchewan,” Walker said, explaining that some officers will utilize the tools they’ve learned from the course within a matter of weeks.

The final part of the course takes place Friday, with a session involving soft-tissue, Walker said.