When she was a kid, Emily Bryce would dress up with her friends for the midnight release of the latest Harry Potter book, or she’d come home excited to be learning about imaginary numbers in math class.

But in December, not yet at her 27th birthday, Bryce died, likely struggling to breathe, of a drug overdose in a Regina alley.

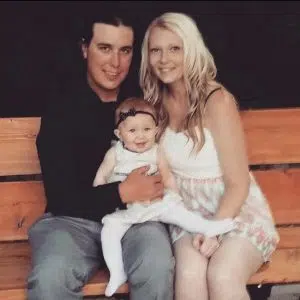

Just a few years ago, Christopher Salateski was teaching his youngest how to skate at just three years old. But last November, Salateski died of a drug overdose, found by his partner in the bathroom of their family home.

Bryce and Salateski are just two of 340 people who are confirmed or suspected to have died of drug overdoses in 2020 — a higher number than the province has ever seen.

As Saskatchewan has dealt with the COVID-19 pandemic in the last year, another crisis has taken a back seat — deaths by drug overdose.

In 2020, there were 273 confirmed drug overdose deaths in the province — 96 more than in 2019 — with another 67 suspected cases waiting to be confirmed.

This year hasn’t been any better, with 125 drug toxicity deaths suspected and 46 confirmed in just the first 153 days of the year.

In this series, Hidden Crisis, we get to know the people in the middle of the crisis, those who’ve died, those left behind, and those who are tasked with helping stem the flood of bodies.

Emily Bryce

Degen Stevenson is Emily Bryce’s mother. She remembers Bryce as very funny with a thirst for knowledge.

“She was such an awesome kid. She was extremely clever and very, very smart,” Stevenson said with a smile in her voice.

Stevenson told stories about Emily bringing home physics books to read and diving into novels like The Fault in our Stars or the Harry Potter series.

“When she was really little we went to all the Harry Potter book releases and I’d take her and we’d be there at midnight so she could get her book and she’d be all dressed up with her friends as different characters,” said Stevenson.

Stevenson said Bryce had a bright future, but believes her daughter somehow got into drugs in university.

For the next several years, Bryce struggled with her addiction. Stevenson said she tried to bring her daughter home and help but it wasn’t a safe situation for her other children.

Stevenson lives in Lethbridge, but eventually Bryce moved to Saskatchewan and got support from family here. Her aunt, Brenda Johnston, said she once had to demand help from a rude doctor in Weyburn.

“I got very angry with him and said I wasn’t leaving until we actually could access a counsellor,” said Johnston.

Bryce was able to get into detox and rehab but slid back into addiction each time.

The last time Stevenson saw Bryce was in summer 2018 in Regina, where they met for lunch. Stevenson said she could tell things weren’t good.

“She had so much makeup on, trying to hide it, but it’s July and she was wearing long sleeves. She had sores on her arms … and you could just see it that she was in bad shape then,” said Stevenson.

But instead of pressing Bryce on it, Stevenson chose to ignore it.

“We had an amazing lunch and just a visit,” she said. “And we laughed and we talked and we just shared as much as we could.”

Stevenson said it was nice to have that last day; she thinks about it a lot.

Stevenson heard about Bryce’s death from a community support worker in December of last year.

“We always expected Emily to not make it. I think what shocked me and my husband the most was how hard we grieved, and still are. I know I haven’t made it a day yet without crying,” said Stevenson.

“I think what shocked me and my husband the most was how hard we grieved, and still are. I know I haven’t made it a day yet without crying.”

“I thought that, when the time comes, because I’ve been grieving her for so long, I didn’t think it was going to hurt this bad but guess what, it really (…) hurts.”

The first line of Bryce’s obituary read: “Emily Colleen Bryce died alone in an alley on Tuesday, December 8, 2020 at the age of 26 years.”

Stevenson said they worded it that way on purpose.

“We couldn’t use those euphemisms, we couldn’t sugar-coat it, we couldn’t say she died peacefully … we both needed that honesty out there,” she said. “If we keep being shameful of these sorts of things, we’re not going to make change.”

Johnston said there’s a lot of guilt still.

“We have to live with knowing that even though we tried to get help, we didn’t get help … When Emily passed away I’m thinking, ‘Oh, we should have done this, we could have tried this, we should have done this.’ It’s a very difficult thing to live with,” said Johnston.

Chris Salateski

Aleesa Blight met her future partner Chris Salateski seven years ago.

“Right from then, we were inseparable. We ended up moving in together fairly quickly. And the relationship was really good. We got along really easily,” said Blight.

From the beginning, Blight knew Salateski suffered from substance abuse issues. He’d been in a serious car crash, crushing one of his hands, years before and was prescribed heavy painkillers on which he became dependent.

“I just kind of went, ‘Whatever.’ You know, people have issues. It’s nowhere for me to judge,” said Blight.

When they started going out, Salateski was on a methadone program and it helped him not go into withdrawal. But Blight said he was struggling with his mental health.

“There were times where there would be stress or issues at home with raising kids and the stress would get to him, and his coping mechanism was, ‘Well, I’m going to turn and get high,’ ” she said.

However, Blight said his issues didn’t define their relationship – they travelled, loved art and music, and were both active people.

Blight remembers Salateski played any type of sport but especially basketball and hockey, and he was a really good skateboarder — even being sponsored for it when he was in high school.

She said he was hard-working and was very family oriented. She said their kids all have fond memories of Salateski – their five-year-old daughter remembers them having root beer floats together and making forts in her grandma’s living room.

“Yes, he was using drugs, but he was still able to be the family man, he was still able to be there for me, for his children, he was still able to hold down a good job and provide for his family,” said Blight.

Right before Salateski died, he got into detox again but it was a two-month wait to get into a treatment centre. Blight said when she heard that, her heart sank.

“I’m like, ‘Oh great, he’s going to be at detox for two weeks, the max he’s allowed to stay, and then what? Then he’s released and then he has to come back home,’ ” said Blight.

He did come home but quickly relapsed.

The morning in November when Salateski died, Blight said she was getting ready for work. By the time she came downstairs to pack lunches for the kids, she found him in the bathroom.

“There was nothing I could do, I called 911 … I had a Naloxone kit and so I did just as I was trained to do, I administered the Naloxone but unfortunately it was too late and Christopher had already passed,” explained Blight.

“It was really hard, something that you won’t forget, seeing your loved one, your spouse, the father of your children just gone.”

“It was really hard, something that you won’t forget, seeing your loved one, your spouse, the father of your children just gone.”

Blight said Salateski taught her a lot: Unconditional love, and how to be more open-minded and more empathetic.

“The one thing that I admire about Chris the most is that in times when he found it hard to love himself, he never lacked showing me or our kids or his friends and family love. He always knew how to show love,” said Blight.

She said losing Salateski created a hole that will always be there.

“(Addicts) are normal people, they have purpose, people love them, they love people, they have families that care about them, they’re not nobodies,” she said. “I just feel that bringing all these issues to light and to talk about it, maybe it’ll help the next person.”

Hear more of their stories here.