Damon Grant would have been celebrating his 49th birthday Sunday.

Instead, his family now sits with only memories of the Weyburn man. The former nurse’s aide injured his back in 2000 on the job, leading to an addictions cycle that saw him struggle with the use of hydromorphones, fentanyl, fentanyl patches and, in the end, anything he could get his hands on.

Since January 2020, 420 Saskatchewanians have died of either confirmed or suspected drug overdose. That includes 75 in 2021, including 36 in the month of January, and an additional 39 in February.

Grant’s wife, Janelle Kincaid, said he was one of the 36 deaths in that first calendar month.

“The week before he died, I had him so close to saying yes to rehab. He knew he could no longer live that lifestyle, nor did he want to live this lifestyle. Fentanyl had such a grip on his mind and his body that just the sheer thought of going into withdrawal was terrifying. The aches, the pains, the shakes, the chills, the fevers — it is probably the worst thing that I have ever seen,” she told 650 CKOM on Friday.

In 2005, Grant was told by his back surgeon that surgery was his next option after the injury. He was declined by the worker’s compensation board because of it being “only soft tissue” damage, which Kincaid said escalated everything he was dealing with in his battle with addiction.

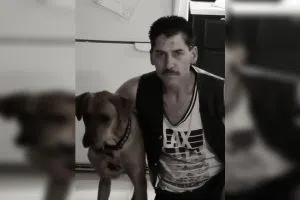

Damon Grant and his dog pictured. (submitted/Janelle Kincaid)

The addiction worsened by 2011, leading to Grant moving into the garage at his family home because Kincaid had kicked him out of the house. In April of that year, Grant found himself on a plane to British Columbia — his original home — for detox and rehab. Three years later, Grant relapsed.

In 2016, the back surgery finally happened, but that started another cycle of addiction. Kincaid said it then became snorting ground-up pills, injecting fentanyl and sucking on the fentanyl patches. He ended up getting clean again before another relapse in 2018.

On Dec. 3, 2019, Kincaid said she left her husband after she had to do CPR on Grant for the first time after an overdose.

“Things just escalated. (I) tried to get him into rehab, (he) wasn’t ready (and) until they are 100 per cent ready to get help, you can’t do anything for them,” she explained.

Kincaid said on Jan. 13 of this year, Grant overdosed for the last time: “He died at 1:50 that morning, on the 14th.”

Picking up the pieces, family left searching for help

Kincaid said she spent a lot of time trying to find a place for Grant to enter rehabilitation and detox in Saskatchewan, sharing another story of the 2018 relapse.

L-R, Damon Grant, Janelle Kincaid, and daughter Megan and son Dylan pose for a family photo. (submitted/Janelle Kincaid)

“It was my daughter that brought everything to light. She’s like, ‘Mom, he’s using again … you’re just not seeing it.’ All the signs were there, but I was ignoring it. I didn’t want to believe it. Having him so close so many times, (I) would spend endless hours calling rehab after rehab, detox after detox centre,” she said, before explaining her struggles with finding a spot.

“‘Can I get him in?’ (They would say) ‘No, we don’t have any beds right now.’ (I’d say) ‘Well, when can I get him in?’ (They’d say) ‘The earliest would be two weeks to a month.’ (I’d say) ‘Well, that’s not going to do. I need tomorrow. I need tonight.’ … It was probably one of the most discouraging feelings ever, being helpless, knowing that he wanted to get it, and (there were) just no beds, no treatment centres. Saskatchewan needs to seriously up their game where addiction comes into play. They really, really do.

“It’s nothing to be ashamed of. There needs to be more awareness, more education and more availability to safe injection sites, or needle exchanges and not the back-door, shady deals.”

Losing a loved one at any time is difficult, yet the days and months following Grant’s death have been tough on Kincaid and her two children.

“(It’s been) lonely. I miss my best friend,” she said, choking back tears. “Even though we were separated, I still loved him. I wanted nothing for him other than to get clean. His kids miss him. His dog misses him. His family is distraught.

“His kids were his world. He had a heart of gold. He would do anything and everything for somebody: Give him his last five bucks or the shirt off his back. He always wanted all of his friends who were in the scene to get out and get help, but couldn’t do it for himself. He struggled with addiction since I first met him. It was alcohol and it was gambling, then it was alcohol again, then it was drugs.”

‘It’s not just a big-city problem;’ mothers band together to end the stigma

Kincaid said she remembers in the time leading up to Grant’s death that just a simple drive downtown would open her eyes as to just what was going on in the city’s streets.

She said he would point out people, saying, “That’s a crackhead,” and, “That’s a methhead.”

“He’s pointing to these people that I know every day,” she said, before explaining it shocked her. He then told her more about who was using, and how no one sees what’s going on.

“(He’d say) ‘If you think that your neighbour down the street isn’t doing it, you’re sadly mistaken. Everybody’s doing something or another. It’s always the ones you’d least expect.’ ”

Because of this and other instances, Kincaid said she carries a naloxone kit with her wherever she goes.

“We’ve had three or four overdoses in either the parking lot or bathrooms of the bars or restaurants here in town,” she said. “It’s bad. We just recently had a fellow lose a bag of needles in the parking lot, and a customer brought them in, into the store.”

Denise Kennedy is one of Kincaid’s friends. Kennedy also has experience with addictions; her daughter Ayla has been in and out of rehab for more than a decade.

Kennedy said her daughter’s addiction issues really took a turn when she turned 16 and found out she was free to leave home with no repercussions.

“She always said, ‘I won’t ever shoot up, I won’t ever shoot up,’ and well, one thing ended up leading to another,” the mother explained.

“It’s been constant, up and down up and down. She wants to get help, she doesn’t want help, it’s just that pattern — the rollercoaster.

“Before her addiction, she was a good student. Very smart, very caring and loving. She was involved in cheerleading … She was a typical kid. I mean, yeah, she got in trouble once in a while but kids learn from it so we move on from it. She was just the sweetest person. She still is — just not when she’s using. She can be very vile and very nasty. It’s not a pretty thing to see.”

A push to get naloxone into the community

The two mothers said drugs have become more prevalent in the community, but they want to bring the discussion out into the open, and “bring awareness to it (so) it will stop the silence.”

“Addiction hates exposure, and recovery demands it. We need to bring it out in the open and talk about it, and make it a normal part of the discussion,” Kennedy said.

“Addiction doesn’t discriminate … It doesn’t matter. It’s everybody and it affects everybody.”

Denise Kennedy’s daughter, Ayla, has struggled with addiction throughout her life, her mother told 650 CKOM. (submitted/Denise Kennedy)

Since Feb. 1, Kennedy said she has distributed 100 naloxone kits to people in need throughout the city. She received the training because of her daughter’s addiction, and through word of mouth, many have been reaching out.

“They would contact me on Facebook (asking), ‘Hey, could you bring a kit?’ … So I just started dropping it off and now I got a cellphone for free, and I plan on hooking it up as pay-as-you-go and having a number that they can phone so that I could get it to them instead of relying on police or the ambulance or waiting until Monday when Addictions Services open again. This way, they have quick access to it. Even right now, the pharmacies can’t give them away for free,” she said.

“You can buy them … but you can’t get them for free. So I thought why not do this? We’re a small enough city that I can handle doing this on my own.

“Every business in town should have it,” Kennedy said before Kincaid offered her take.

“Right alongside the defibrillators. (The naloxone) should be right there, ready to go,” Kincaid said.

“(Saskatchewan’s addictions crisis is) not just a big-city problem, it’s everywhere. It’s in your towns, your villages, back-country roads, farms, you name it — it’s everywhere.”

The women said they want to change the way people look at addictions, especially in the small-city setting like a community such as Weyburn. Kincaid said the addictions issue within her life affected the entire family and everyone associated with Grant’s life. She added that she wished things were different and that people looked at the issues in a different light.

“I just wish people would say, ‘Hey, I need help,’ and be comfortable for asking for help. But there’s such a (stigma attached to) it, they hide it. They want nothing to come to light. They want to seem perfect, but yet everything’s not perfect,” she said.

Both Weyburn women said the conversation needs to change, with Kennedy summing up the crisis in just six simple words: “Everybody’s addict is somebody’s loved one.”