There could be a big change coming to the way historians and art curators uncover the past, thanks to researchers at the Canadian Light Source (CLS) in Saskatoon.

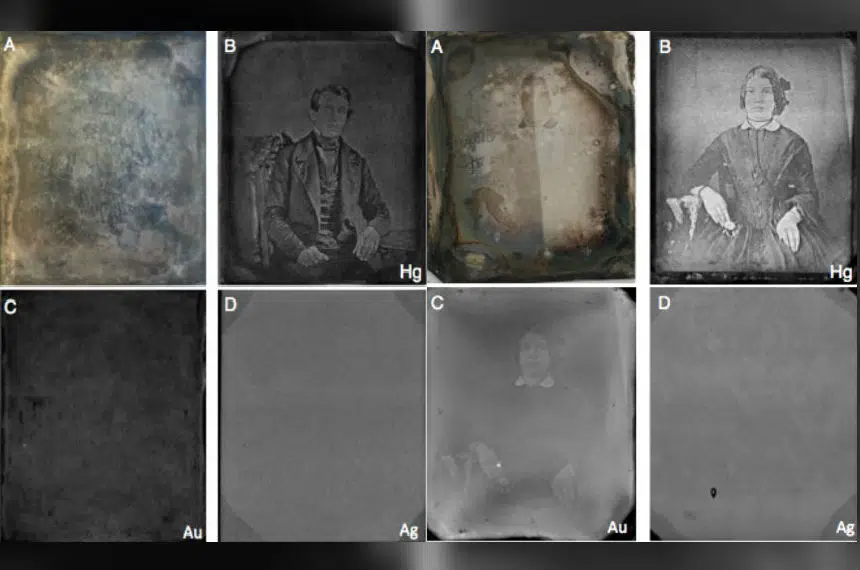

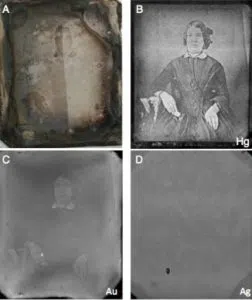

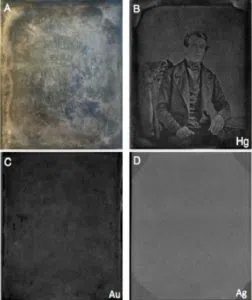

Working on daguerreotypes, the earliest form of photography that used silver plates and mercury vapor, scientists were able to use light to see through centuries of decay as if the image was new again.

Research that details how two photos (taken possibly as early as 1850) from the National Gallery of Canada`s photography unit were transformed from blank, grey slabs of steel into works of art was published last week in Scientific Reports.

One photo uncovered the portrait of a man. The other, a portrait of a woman.

Researchers at the Canadian Light Source worked with students at Western University to uncover photographs like this one lost to decades of deterioration on June 25, 2018. (Submitted / Canadian Light Source)

“These objects being metal plates, have corroded and tarnished similar to your silverware that you would have at home,” Madalena Kozachuk, lead author of the paper, explained. “If it’s tarnished and you don’t know anything is behind it, then there’s no history to investigate.”

“Now we have a whole realm of history that was unknown previously that we can possibly tap into.”

Researchers at the Canadian Light Source worked with students at Western University to uncover photographs like this one lost to decades of deterioration on June 25, 2018. (Submitted / Canadian Light Source)

The project became the brainchild and graduate thesis research of Kozachuk, a graduate chemistry student at Western University. She originally wanted to pursue research into Franklin’s lost expedition in the Canadian Arctic.

That was until she met the head conservator at the National Gallery who nudged her towards daguerreotypes.

“I’ve always been a lover of photography, so to be able to look at (the images) from under the scientific lens is extremely rewarding,” Kozachuk said.

Ian Coulthard, a scientist at the CLS in Saskatoon and supervisor on the project explained the science behind the discovery.

“Through the use of the synchrotron and using X-rays, we’re able to see through the damage,” Coulthard said. “Looking for the small amount of mercury that is in these image particles, we were able to create an image of what the photograph looked like to the naked eye when it was first taken.”

It all starts by focusing the x-rays down to levels similar to the smallest objects the human eye can differentiate, around 10 to 20 micrometres.

That small beam runs across the sample horizontally and vertically, collecting information as those x-rays move across the mercury atoms on the surface of the steel.

Then, a map is generated from the intensity of the mercury seen on the scans for a recreated image.

“What you see in recreating the image using the mercury fluorescence, translates directly into what was seen by the naked eye when the photograph was first taken,” Coulthard said.

When the research project was first conceived, the only objective was to learn more about the degradation and tarnish on the photos, to help improve conservation. Now, art curators could potentially uncover whole chapters of unwritten history.

“I’m still amazed that we were able to see what we are to see, it was a surprise,” Coulthard said. “We weren’t expecting to see this sort of result when we started this process.”

The glaring problem with this discovery is the access. It’s not like every public library has a synchrotron in the back room.

To that end, Kozachuk and Coulthard hope their research is a stepping stone to a more viable recovery process in the future. Until then, we could see more works of cultural importance make their way to the CLS’s laboratories.

When asked about the implications of their discovery, Coulthard couldn’t underplay the role this research might have.

“It’s very important, especially from a Canadian perspective, because the history of photography and the history of Canada are so closely intertwined that you have all these early photographs, some of which could potentially be lost to history because of this damage.”

“Recovering those images is also recovering little pieces of Canada’s history.”

Thanks to the hard work of graduate student researchers and a couple of Canadian institutions, recovering Canada’s past is another reminder of how the CLS is progressing the world forward and helping realize what is possible.