Early evening on September 26, 1990 the last of a group of Mohawk warriors left their encampment and ended a 78-day standoff called the Oka Crisis.

At the centre of the crisis was a proposed expansion, without consultation, of a golf course and a development of condominiums on traditional Kanehsatake Mohawk land which included a burial ground.

The Kanehsatake began with a peaceful blockade to prevent the expansion, but on July 11 the Quebec Provincial Police were called in and the situation escalated into a shootout. A 31-year-old police officer was killed.

“I was driving to work and I had the radio on and they had news that there had been a shootout in Kanehsatake,” National Film Board of Canada (NFB) documentarian Alanis Obomsawin, said.

“All this time everybody thought it was going to be two days, maybe three days.”

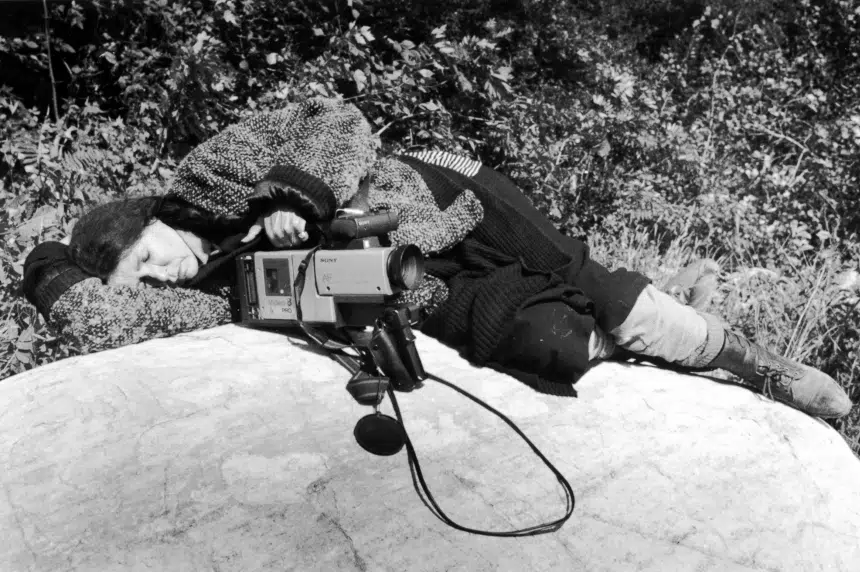

Obomsawin is a member of the Abenaki Nation and has been making documentaries for over four decades with a focus on the lives and concerns of First Nations. She made four films about the crisis including the first “Kanehsatake: 270 Years of Resistance” released in 1993 which won 18 international awards.

“We started to document what was happening. Police were fighting with people and it was really crazy. So I said to the camera person, let’s just document this,” she said. “It was shocking but to say I was surprised? No. There had been so many problems concerning land issues here and it was the first time that a community resisted as much as that.”

Obomsawin and her small crew began heading in and out of the community to film but one day a police officer would not let her through.

“They called me a ‘goddamn feather face’ it was awful,” she said.

After speaking with the officer’s superior, she was allowed in but decided that she would stay behind the police barricades to make sure she wouldn’t be forced out.

“I had to sleep outside with all the other journalists. I didn’t have a sleeping bag or anything like that. I used a garbage bag to make a tent between two trees and it was cold at night,” she said.

“Some days I was worried and I would think of my daughter, she was 20 years old … I was looking at the little children there and I was like ‘oh my god’, they are too small it would be terrible if they lost their parents.”

The anxiety was apparent behind and in front of enemy lines as the police were replaced with the army and the nearby Kahnawake Mohawks blockaded the Mercier Bridge in solidarity.

“I knew I had to document this to the end but there were times in September when it came very close to a shootout. When the soldiers and the warriors were insulting each other,” Obomsawin said.

“If one shot had been on either the army or the warriors then we would have been finished. It would have been terrible. You never knew what was going to happen from one moment to the next.”

After the Kahnawake reopened the bridge, it set a path to the end of the crisis, according to Obomsawin. She said the Kanehsatake felt “betrayed.” But it would take until September 26 for the crisis to end.

“The traditional chief told me that they were leaving,” she said. “I saw the warriors burning their guns and getting rid of all those things. They were really ready.”

Obomsawin said the warriors also spent time with two traditional chiefs having ceremonies which helped them prepare for peace.

“They were so different after that, the warriors. It was a different talk and a different way of being. They became really part of the land, where as before they had the guns, it changed totally,” she said.

“I think if the (chiefs) hadn’t been there I can almost say for sure there would have been a shootout.”

Around 4:30 p.m. the warrior flag was lowered and the last of the Mohawk, including women and children, walked towards the military lines putting an end to the 78-day standoff.

Now 83-years-old, Obomsawin said that the struggle over land rights has happened to many reserves and the resistance of Kanehsatake changed the conversation for the whole country.

“In a lot of ways it has educated a lot of people. At first a lot of people really hated the Mohawks and put them down, but now it’s a different way of talking about this history,” she said.

“And they didn’t lose, it’s a contrary, they won. They never made the new nine-hole golf course. Those houses they wanted to build around never were built, so they did win.”

Watching movements like Idle No More and aboriginal land rights victories like the 2014 Supreme Court ruling granting title to more than 1,700 square kilometres of land in B.C. to the Tsilhqot’in First Nation, Obomsawin is optimistic about the future.

“I see so much incredible things happening that I am more than encouraged. There is such a strong movement with a lot of people, mainly young people,” she said.

“I think it’s the realization of a lot of young people that have had a lot of trouble, whether in alcohol, drugs, or suicide, and there is an awake that is happening in their minds and their hearts.”

She said the youth are connecting with their traditions and finding strength in who they are.

“I am so happy that in my lifetime I will have seen this because we are going to a very different road now,” she said.